Ancient Oasisamerica, no. 2

United States History

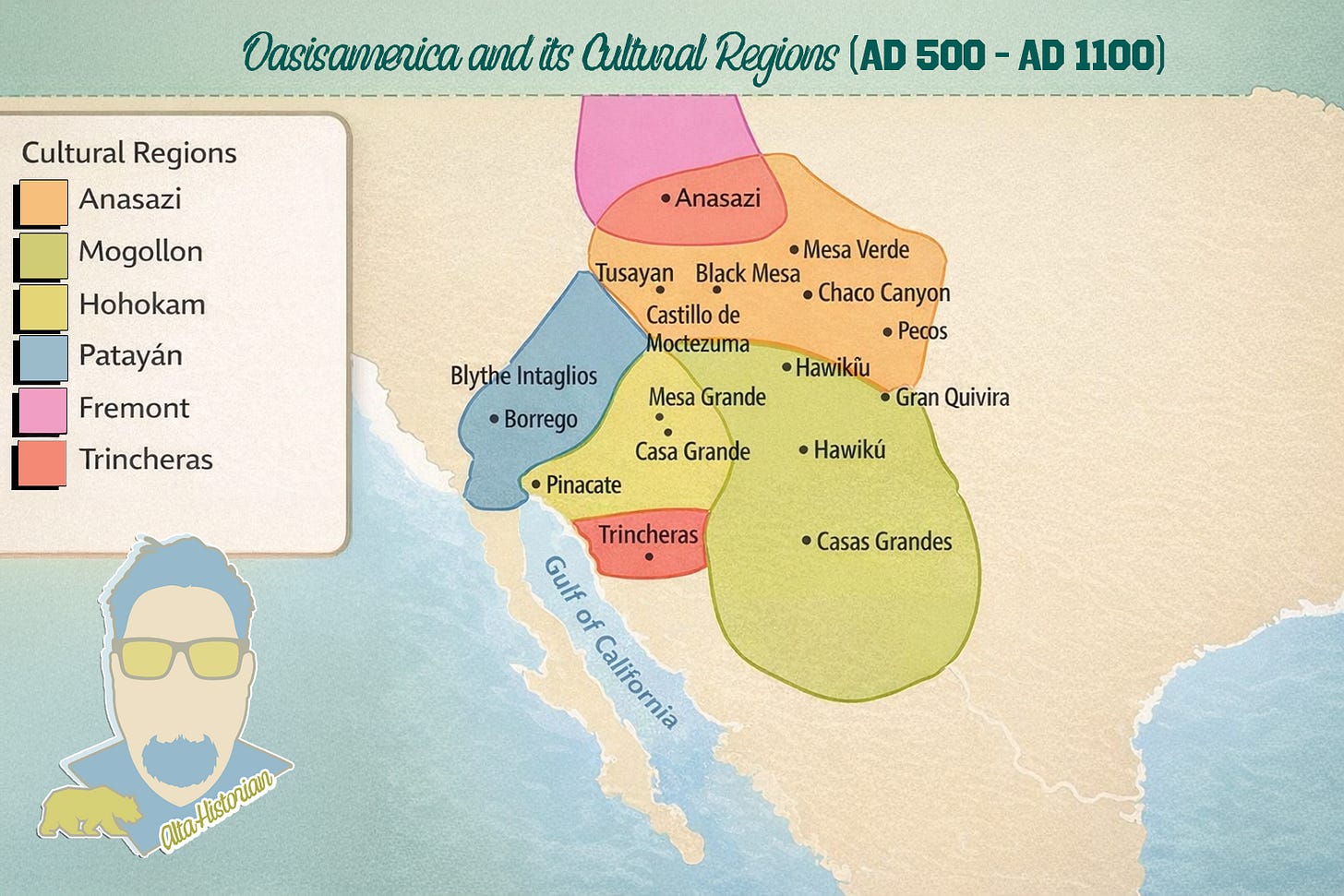

As you already know, if you have read number one of this series, I like the term Oasisamerica—but it has its limitations. In the territory that would become the Pueblo culture, the Spanish would encounter the (and name) Pueblo, which is a Spanish definition of this region. We will start with perhaps one of the most famed and influential cultures of the ancestral pueblo homeland, the Anasazi.

Anasazi

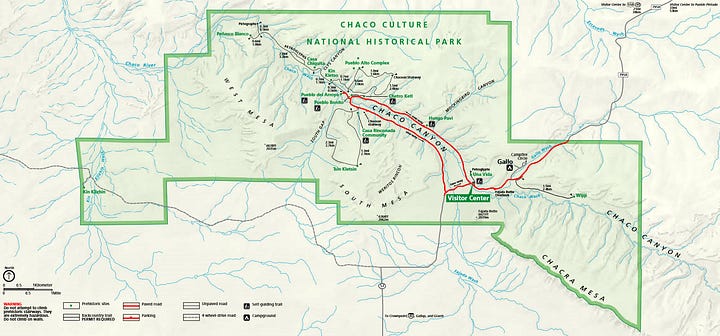

The Anasazi are among the more prominent of these cultures because places like Chaco Canyon were the centers of much of the “centerplace’s” economic and cultural significance. Their name, Anasazi, is a bit controversial — some say it means the “Ancient Ones,” while others trace it to the Navajo words meaning “Ancient Enemy” or “Ancestors of the Enemy.” There is nothing I like more in history than a good controversy over a multi-thousand-year beef. Regardless, the name persists in scholarship, and I guess it is the same with the Aztecs (who are actually the Mexica) — they never called themselves that, nor did the Olmec, and I guess there are copious examples.

I digress.

The Anasazi are divided into two major phases. The first is the Basketmaker Period, roughly from AD 100 to AD 750. The Anasazi emerged around AD 100, but, as is the case with all peoples, their roots extend back to 1500 BC, to the Archaic Period (8000 BC - 2000 BC), when early Pueblo people formed part of the Cochise culture. The second period is the Pueblo Period, where the settelment of villages occurs, along with the building of monumental architecture, with their decline coming roughly at the time of AD 1600 — well after the conquering of Tenochtitlan (1521) and Fray Marcos de Niza (1539) makes the first reported Spanish reconnaissance into the region in search of Cíbola — the mythical Seven Cities of Gold.

Anasazi cultural territory encompassed roughly 30,000 square miles across what are now the states of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. Some of the tribes the Anasazi are the ancestors of may sound more familiar: the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and Laguna, among others. These groups would later clash with Spanish colonial forces in the late sixteenth century, notably during the Francisco Vásquez de Coronado Expedition (1540), which would spark conflict over multiple centuries.

Mythology (and I use this term loosely because more and more of these mythological stories are appearing true with technological breakthroughs) — anyway, mythology holds that the Pueblo peoples emerged from Mother Earth as cartakers, wandering in search of the Center Place until a strange encounter with Maasaw (MAH-sah), the creator and caretaker of the earth. They made a covenant with Maasaw, and in that covenant were shaped their settlement patterns, spiral iconography, and monumental construction.

Mogollon

The Mogollon culture, south of the Anasazi in the mountainous borderlands of southern Arizona and New Mexico, thrived between AD 300 and AD 1300. They emerged from the Cochise culture at roughly 300 BC and were among the earliest farmers in the region. The Mogollon used pottery to store tobacco and cotton, along with their staple crops of the Three Sisters — corn, beans, and squash — and hunting and gathering supplemented their diets.

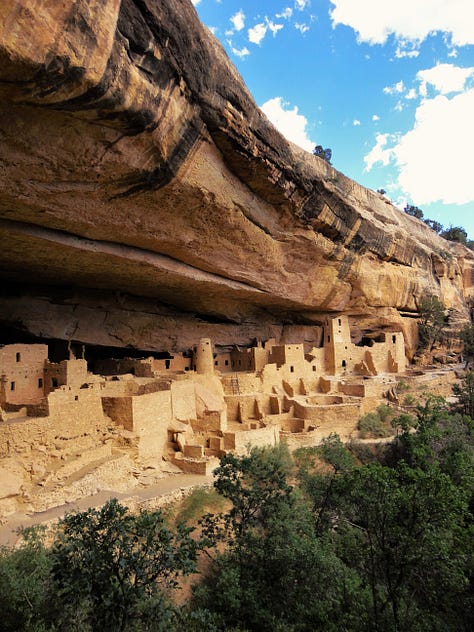

Around AD 500, the adoption of the bow and arrow (which occurred throughout North America) improved hunting efficiency, and Mogollon settlements were located along natural ridgelines for defense. I have provided an example of Cliff Palace below. Though the Cliff Palace is in Anasazi territory, and the other is Gila Cliff National Monument in Mogollon territory, you see the shared innovation. At Mesa Verde, cliff dwellings appeared in the late AD 1100s. More than 4,000 sites have been recorded, including roughly 600 cliff dwellings.

Like other Pueblo peoples, they lived in pit houses with ceremonial centers called kivas, and pit houses in the same style, sunk into the ground and built upward to keep cool in the summers and warm in the winters. When people claim there was no civilization in North America, ask them how much they would pay to live in the kiva pictured below.

At roughly AD 1100, the Mogollon architecture shifted to above-ground adobe pueblos, which many of the Spanish Missions of the Southwest were built using this “Pueblo” style — in many ways, a silent homage to the ancestral Pueblo people. This, along with cotton, feathers, animal fur yarn, basketry, and a wide array of stone, wood, bone, and shell artifacts, defined the material culture of the Mogollon and other regional cultures.

Hohokam

The Hohokam culture has the second coolest name in the region (according to me 🤓) — in the Pima language, it means “The Vanished.” Their culture flourished between 100 BC and AD 1500 in the southern and western parts of what is now Arizona. Centered in the Gila and Salt River Valleys, the Hohokam were responsible for engineering some of the most impressive irrigation systems in prehistoric North America. Their primary settlement, Snaketown, was near what is now Phoenix and included roughly 100 pit houses. Another major center was Point of Pines.

Within the Hohokam culture, we see the influence of Mesoamerican culture, as evidenced by ballgame courts and rubber balls, suggesting sustained trade between the two regions. The Hohokam culture was also an innovator, and around AD 1000, they developed shell-etching techniques using saguaro cactus fruit, a plant native to the Sonoran Desert. However, the centerpiece of their culture is seen at Pueblo Grande, where canals stretching 150 miles irrigated 250,000 acres — supporting dozens of communities for roughly 600 years. The downfall was in part due to their success with agriculture and irrigation, while increasing raids eventually forced abandonment, fields were waterlogged, and populations moved toward the Gila River.

Athapaskan Migration and Conflict

Who were the ones raiding the Hohokam and other sedentary agrarian cultures? It is said that the Athapaskan (ATH-uh-PASS-kin) peoples, the ancestors of the Apache and Navajo, who had migrated south around AD 850. They are part of the Na-Dené language family, and their linguistic family tree extends from Alaska to the Great Plains of North America. As nomadic hunters and raiders, the Apache and Navajo groups played a critical role in regional political, social, and economic dynamics. These groups relied primarily on hunting, but when hunts faltered, they turned to agrarian groups to supplement their diets and economies.

When Europeans reintroduced horses (the horse is actually indigenous to the Americas, going extinct some 12,000 years ago), they became elite riders — this, of course, expanded raiding and regional tribal rivalries. In fact, the Comanche attempted to exterminate the Apache for decades. Of course, Pueblo societies already had adaptations, such as cliff dwellings, but defensive adaptations were not a permanent fix and were rather impractical. These pressures expanded trade networks but also hardened architectural and military responses.

Architecture, Conflict, and Collapse

The Basketmaker period brought mastery in weaving, sandals, and plant-fiber technology. By AD 200, small pit houses began to appear, and by AD 500, clusters of twenty to eighty structures dotted Chaco Canyon. These were not temporary camps; they were the beginnings of permanent, organized space.

Between AD 800 and AD 1150, Chaco Canyon emerged as the architectural and ceremonial center of the ancestral Pueblo world — a place where astronomy, trade, ritual, and administration converged. Adobe pueblos began to spread after AD 700, signaling shifts in community planning and social coordination. Construction ceased between AD 1150 and AD 1250, followed by large-scale dispersal. Agriculture sustained these communities for centuries, but by the late AD 1200s, southward migrations accelerated.

Violence, often romanticized away in modern imagination, was not absent from this world. As Polly Schaafsma (SHAFF-smah) notes, the absence of warfare would be the anomaly, not its presence. Osteological evidence confirms conflict stretching back two millennia: scalping, trophy-taking, and the mutilation of the dead. Burned villages, rock art depicting combat, and mass killings align with phases of migration. After AD 1200, cases of cannibalism appear at Sand Canyon Pueblo and Castle Rock, and at Casas Grandes. Archaeologists have documented what may be the largest prehistoric massacre in the Southwest.

Climate layered itself onto this human drama. The Medieval Warm Period produced severe droughts, tightening the margins for energy and subsistence. Scarcity sharpened competition. By AD 1300, demographic shifts, new settlement patterns, and ideological transformations reshaped Pueblo society.

These pressures were not confined to a single region. The Mexica migrated south from Aztlán as drought emptied portions of the interior West, funneling peoples into new ecological and political corridors. Warfare, fertility, rainmaking, and religion became inseparable — a single package of survival and meaning.

Oasisamerica, in short, was not simple, peaceful, or static. It was a world of farmers, traders, warriors, artists, and believers, adapting in real time to climate, scarcity, and one another. Like civilizations elsewhere, its peoples fought, created, exchanged, and sought purpose. And as with all ancient worlds, we should leave space for what remains unknown — for Oasisamerica still has more to reveal — I hope.

Bibliography | Notes

Archaeology Southwest. “Patayan Culture.” https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/ancient-cultures/patayan/.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Ancestral Pueblo Culture.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ancestral-Pueblo-culture.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Cochise Culture.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Cochise-culture.

Chacón, Richard J., and Rubén G. Mendoza, eds. North American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007.

Christianson, Justine, transmittal documentation; Historic American Engineering Record, creator; Texas Tech University Water Resources Center, sponsor. “Hohokam Irrigation Canals, Pueblo Grande Museum, Phoenix, Maricopa County, AZ.” Library of Congress (HAER), documentation compiled after 1968. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/az0627/.

Hämäläinen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Lambert, Patricia M. “The Osteological Evidence for Indigenous Warfare in North America.” In North American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence, edited by Richard J. Chacon and Rubén G. Mendoza, 202–221. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007. https://open.library.ubc.ca/media/download/full-text/24/1.0363040/.

López Austin, Alfredo, and Leonardo López Luján. Mexico’s Indigenous Past. The Civilization of the American Indian Series, vol. 240. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001. https://archive.org/details/mexicosindigenou0000lope.

Mesa Verde National Park (U.S. National Park Service). “Cliff Dwellings.” https://www.nps.gov/meve/learn/historyculture/cliff_dwellings_home.htm.

National Park Service. A Brief History of Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Chaco Culture National Historical Park brochure (PDF). https://www.nps.gov/chcu/learn/upload/Chaco-Brief-History.pdf.

National Park Service. “Fremont Culture.” Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service). https://www.nps.gov/care/learn/historyculture/fremont.htm.

National Park Service. “Fremont Culture.” Great Basin National Park (U.S. National Park Service). https://www.nps.gov/grba/learn/historyculture/fremont-culture.htm.

Neuman, Scott. “Ancient Footprints Suggest Humans Lived In The Americas Earlier Than Once Thought.” NPR, September 24, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/09/24/1040381802/ancient-footprints-new-mexico-white-sands-humans.

PBS LearningMedia. “The Hopi Origin Story.” Native America (PBS), 2018. https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/collection/native-america/.

Roberts, David. “Riddles of the Anasazi: What Awful Event Forced the Anasazi to Flee Their Homeland, Never to Return?” Smithsonian Magazine, July 2003. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/riddles-of-the-anasazi-85274508/.

Schaafsma, Polly. “Documenting Conflict in the Prehistoric Pueblo Southwest.” In North American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence, edited by Richard J. Chacon and Rubén G. Mendoza, 114–128. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007. https://www.academia.edu/52638134/House_of_Shields_Defensive_Imagery_at_Defensive_Sites_in_Tsegi_Canyon.

ScienceDaily. “Localized Climate Change Contributed to Ancient Southwest Depopulation.” December 4, 2014. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/12/141204074309.htm.

UtahIndians.org. “History: The Navajo.” https://utahindians.org/archives/navajo/history.html.

Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. 3rd rev. ed. New York: Facts On File, 2006. https://cmc.marmot.org/Record/.b58763971.

Waldman, Carl, and Molly Braun. Atlas of the North American Indian. 3rd ed. New York: Facts On File, 2009. https://books.google.com/books/about/Atlas_of_the_North_American_Indian.html?id=P2HKD9PgC6wC&utm_.

Wei-Haas, Maya. “New Evidence That Ancient Footprints Push Back Human Arrival in North America.” New York Times, October 5, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/05/science/footprints-tracks-new-mexico-age.html.

Photo Citations

Interior of One of the Dwellings at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico, USA. Photograph. Public domain. Accessed via FHWA (U.S. Federal Highway Administration). Uploaded April 24, 2006.

Rationalobserver. Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park. Photograph. Created June 13, 2015. Uploaded June 13, 2015. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Ekotyk. Inside the Great Kiva at Aztec Ruins National Monument. Photograph. Created April 19, 2017. Uploaded April 19, 2017. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Jw4nvc. Aerial View of Pueblo Bonito. Photograph. Created May 18, 2013. Uploaded December 8, 2014. CC BY 3.0.

United States National Park Service. Map of Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Map. Public domain. Created March 12, 2015. Uploaded March 13, 2015.