Bolívar and the United States

The Works of the Alta Historian

As I prepared for the semester, I was going to leave this course (History of Latin America II) out of the revisions. But, as history often does, it rhymes, and with so much going on in Latin America, I decided that now would be the best time to find the intersection of Latin America’s past with its more recent history.

And on a side note, this course will not be about The Donald, but rather a look at how the relationship between the United States and Latin America has evolved. What has changed? What has remained consistent? What are the motivations of each party? These are the questions we will explore, along with poking, prauding, and, from time to time, debating our ideas with each other.

I hope that this course is unlike any other you’ve ever experienced. I don’t know if that will be a good or a bad thing when it is all said and done — but I am optimistic.

“Mr. Trump’s approach appears purely pragmatic: What is in it for the United States?”

Stronger control of the hemisphere, and particularly Latin America, promises major benefits. Ample natural resources, strategic security positions and lucrative markets are all in play.”

Jack Nicas — The New York Times

The POTUS is calling it the “Donroe Doctrine” now.

That line was meant to be funny. But it also told the truth. Whether he meant to or not, Trump was pointing straight at a very old idea: that the United States sees the Western Hemisphere as its business.

Venezuela did not suddenly fall apart after Chávez died. It adjusted. Inside the country, the government learned when to bend just enough to stay alive. Its citizens knew how to survive on mangos as food production and the economy collapsed under socialist rule. At least that is according to Daniel Di Martino, a Venezuelan‑born economist, writer, and activist, who appeared on the Triggernometry Podcast. Di Martino made interesting observations, and if you are empty on your podcast oil tanker, you can fill up with Di Martino’s interview.

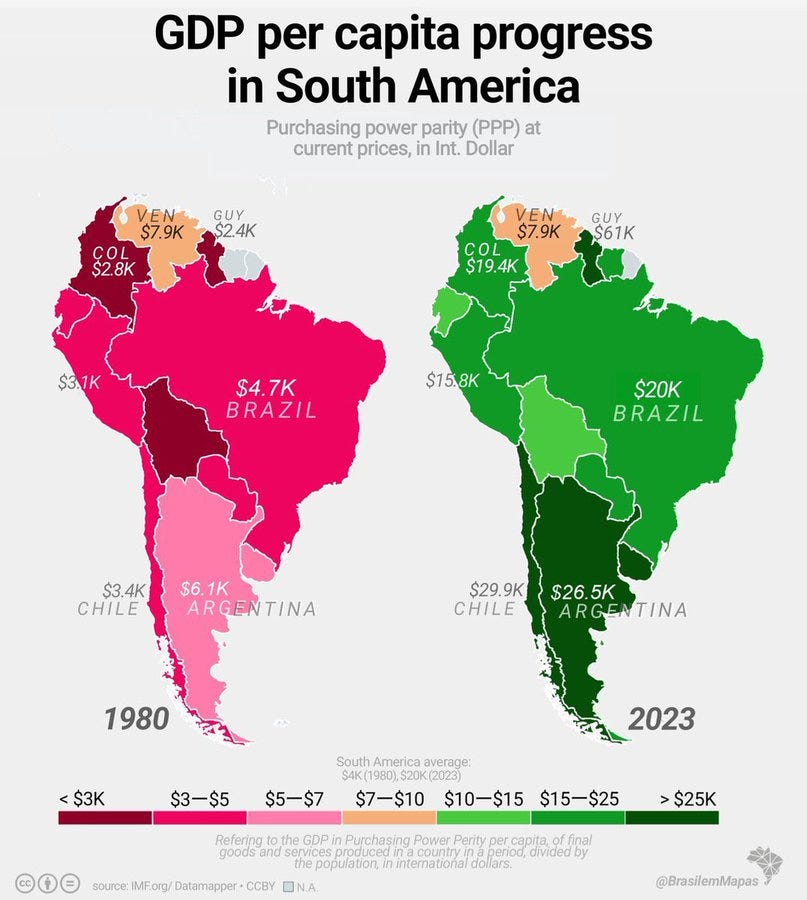

Outside the country, the view of Venezuela hardened. Louder threats. Less patience. More force. Even so, the regime remained standing but appeared more lethargic and unable to move forward as infrastructure crumbled and geopolitical alliances faltered. The state locked itself in place. And that paralysis produced the worst economic collapse Venezuela has ever known — a country with more potential wealth (oil) in the ground than just about anyone else in the world.

“Make Venezuela Great Again” was another slogan, said by The Donald, as the United States has reestablished its foothold in Latin America over the course of the last few years. As Nicas notes in his New York Times article, the roster is deepening:

President Javier Milei of Argentina, for instance, campaigned to “Make Argentina Great Again.” In El Salvador, “President Nayib Bukele agreed to take more than 200 Venezuelan deportees into his nation’s maximum security prison when no other nation wanted them.” El Salvador, Ecuador, and Guatemala all secured new trade deals at the end of 2025 — with Panama holding out — but the wave appears to be set to crash into Latin America in 2026. Bolivia now has centrist Rodrigo Paz (the first non-leftist in two decades), Chile looks to be heading down the same road, Trump has supported a right-wing mayor of Lima, Peru, in his bid for his country’s top spot — Rafael López Aliaga (affectionately known as “Porky”). These types of interpersonal, political relationships are not new.

So when I woke up to a media storm Saturday morning on January 3, 2026 — not the kind Maduro woke up to — but a political one, my thought was “this is a historical moment.” It’s 2026, and the year has started hot, extra spicy. Some of that energy carried over from last year. Some of it, if you listen closely, has been building for decades. I’d argue longer than that. What’s happening in Venezuela is not a Trump story. It’s not even a twentieth-century story. It’s a long story about the United States and Latin America, and Venezuela happens to be the chapter we’re in.

To understand it, you have to go back to Simón Bolívar.

Simón Bolívar is often called the George Washington of South America. Like Washington, Bolívar came from a wealthy, elite background. He fought for independence. He won a war. He resisted crowns. He talked about returning to a private life, but instead found himself building governments. He was accused of ambition. That’s where the overlap ends.

Bolívar fought longer. He traveled further. His war stretched across jungles and mountains, from heat to snow, across distances Americans never had to imagine. The crossing of the Andes alone almost destroyed his army. Men froze. Horses died. Supplies vanished. And then he came down the other side and caught the Spanish completely off guard. It was an extraordinary gamble, and it worked. Kind of.

Bolívar fought both a civil war and a revolutionary war concurrently. He was the president of multiple countries and a founding father of many of them. His revolution began when he was a younger man, only twenty-six, and unlike Washington, Bolívar was not a military man — at first.

Bolívar’s war was not Washington’s war. Bolívar’s life was not Washington’s life. Bolívar could not have won without the compromise with Black and Indigenous soldiers. Freed slaves. Mulattos. Mestizos. Others. His armies reflected the population. That mattered in his delicate approach to revolution. The bloodshed of his revolution was immense. In Venezuela alone, more people died than in the American Revolution and the U.S. Civil War combined.

By the time Bolívar was racing toward Boyacá, his name was already known worldwide. In Washington, leaders like Adams and Monroe were uneasy. The United States was young, prosperous, and deeply tied to slavery. The largest part of its economy depended on it. Supporting a revolutionary army filled with liberated slaves raised uncomfortable questions. Support of Bolívar, as the Americans saw it, could lead to a revolt among their people.

In London, the story was different. Veterans of the Napoleonic Wars were broke and unemployed. Many signed on to Bolívar’s cause. They left England in fine uniforms, with bands playing, only to arrive to fight alongside barefoot soldiers carrying sticks. And the war dragged on. Years of violence passed before Spain was finally pushed out. Even then, the fight was not over.

By August 1818, Bolívar was barely holding on. Spain still controlled much of Venezuela. Earlier republics had collapsed. Bolívar ruled from temporary capitals and exile. He needed more than victories. He needed legitimacy. And the only way to be seen as a legitimate country is through the approval of European powers. There were complexities to this: how could European powers support a republic of a mix of Europeans among a larger mixed group of mestizos, mulattos, Asians, Blacks, and Indigenous people?

Bolívar turned to the United States and asked the young republic of the North to stop pretending neutrality was harmless. He did so in a letter to an informal U.S. representative, named Baptis Irvine.

From Bolívar’s view, American neutrality wasn’t neutral at all. By enforcing laws that punished people who helped the patriots, the United States was quietly helping Spain. Bolívar argued that neutrality ceases to be fair the moment it favors one side over the other.

In practice, American law treated those who helped independence as criminals, handing down punishments so severe they might as well have been death sentences. Bolívar wrote to Baptis Irvine on 20 August 1818,

“I insist that I see no need for a neutral to embrace this or that faction just to keep from abandoning his profession, nor do I think it possible to apply this principle to ports under blockade without destroying the rights of the warring nations. If the usefulness of neutral nations is the origin and basis for allowing them to continue trading with powers at war, the latter not only can advance the same rationale against the common practice of trading with ports under blockade but can also point out the harm that results from the prolongation of a campaign or a war that could otherwise be ended through surrender or through the imposition of a limited siege. Impartiality, which is the essential ingredient of neutrality, vanishes in the act of aiding one party against the clearly expressed will of the other, which justly opposes such action and which moreover has not asked for help.”

This was the turning point. The American republic Bolívar once admired now looked cautious, self-interested, and hypocritical. Bolívar’s deeper problem was structural. How could he bring a republic together as the United States had after its revolution?

North America shared language, culture, and political habits. Latin America didn’t. Spanish rule had been laid over Indigenous societies, imported the African diaspora, and had mixed populations created by combinations of empire and the extreme geography of Latin America. Add the power of the Catholic Church — owner of land, labor, wealth, and influence — and the idea of a clean democratic republic became fragile.

Bolívar decided that American-style democracy would collapse under those conditions. He believed the region needed order before liberty. Strong leadership before elections. Long presidencies to hold things together. In his mind, chaos was the greater danger.

That belief cost him everything.

In the 1820s, he centralized power. He ruled more directly. Opposition hardened. The Convention of Ocaña was supposed to fix Gran Colombia’s constitution. Instead, it exposed how broken the republic already was. Bolívar’s opponents sought a weaker executive and stronger regional powers — much like the system in the United States. No one could agree. The convention fell apart. Of course, let’s not forget that the power of the Catholic Church favored centralized power in the style of Old World Europe — it was easier to navigate, more efficient in some ways, and, most certainly, easier to influence.

Bolívar responded by taking dictatorial authority. Resistance exploded. To many, the Liberator now looked like a threat to the very liberty he once promised. From that moment on, his legitimacy bled away.

He died on December 17, 1830, exhausted and convinced he had failed.

But Bolívar never left.

There are parties named after him. Ideologies built around him. A country carries his name. No one chants Washington in the streets. No one rallies under Jefferson’s banner. But in Latin America, Bolívar still moves people. He is claimed again and again.

Hugo Chávez claimed him. Nicolás Maduro inherited that claim. But the problem in Latin America is that there is no real movement forward without the United States having a say. The result has often been a collapse without collapse — survival without progress — and perhaps that is the dividing line in the dichotomy between Washington and Bolívar, the United States and Latin America’s countries. The United States had no resident superpower to deal with in its hemisphere.

Which brings us back to this morning.

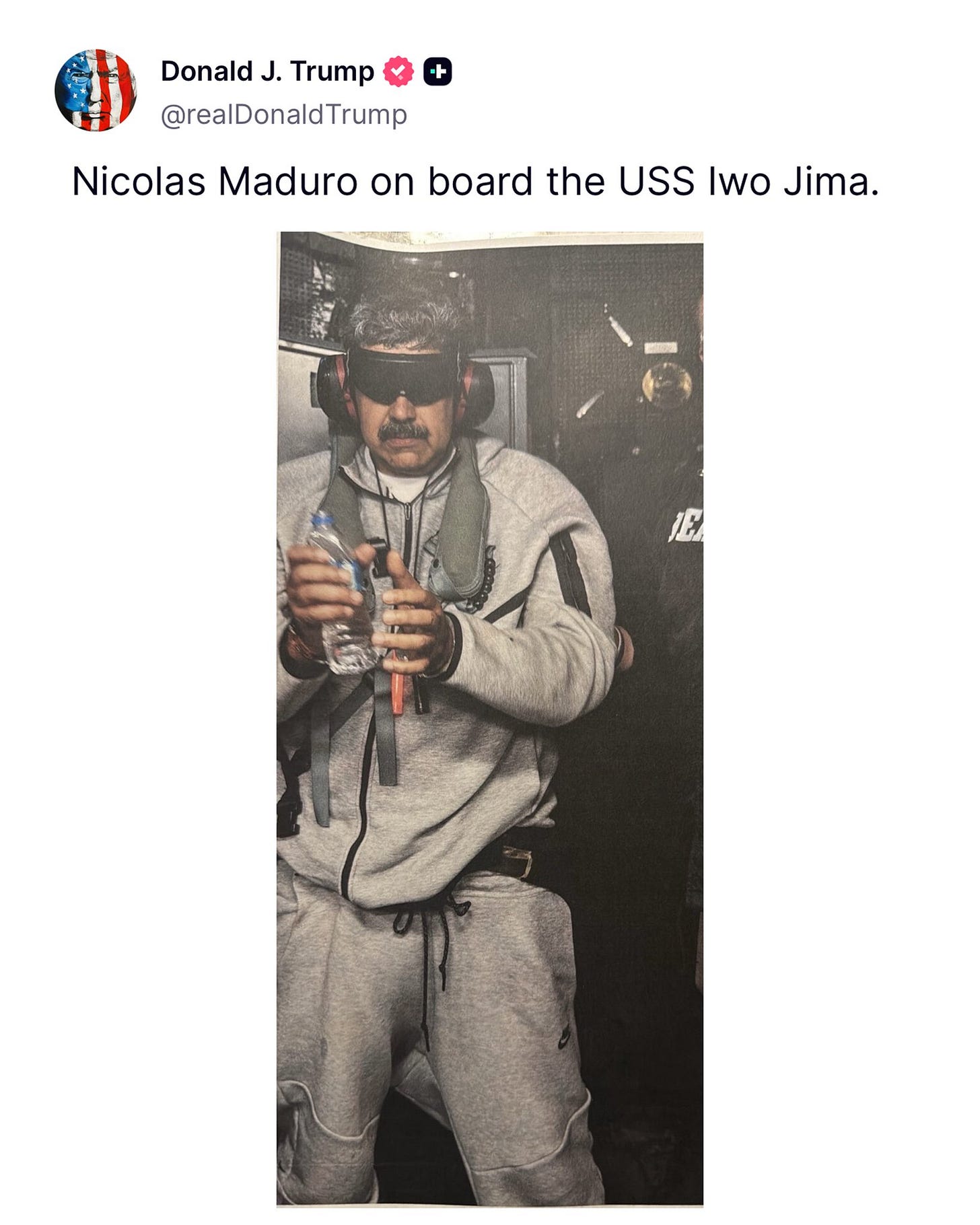

Trump announced Maduro’s capture. Maduro was put aboard the USS Iwo Jima. The cameras rolled. And Trump reached for history.

“They’re calling it the Don-roe Doctrine now.”

The real Monroe Doctrine came later, in 1823, after Bolívar had already soughtout the United States for help and been denied it. But the idea behind it — the belief that the hemisphere belongs to American influence — has been here the whole time, remains strong, and some may argue, is only getting stronger.

This didn’t start today. It didn’t start with Trump. It began when revolutions crossed paths and republics chose their interests.

History didn’t wake up this morning. We did.

Bibliography | Notes

Bolívar, Simón. El Libertador: Writings of Simón Bolívar. Translated by Frederick H. Fornoff. Edited with an introduction and notes by David Bushnell. Library of Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Library of Congress. Marie Arana, “Simon Bolívar: American Liberator” (Webcast Transcript). https://tile.loc.gov/streaming-services/iiif/:service:gdc:gdcwebcasts:13:06:06:kl:u1:60:0:130606klu1600:130606klu1600_640x480_800/full/full/0/full/default.txt.

Nicas, Jack. “The ‘Donroe Doctrine’: Trump’s Bid to Control the Western Hemisphere.” New York Times, November 17, 2025.

Williams, Lillian. “25 for 25, ‘Bolívar: An American Liberator’ by Marie Arana.” Kluge Center — Library of Congress Blog, November 13, 2025. https://blogs.loc.gov/kluge/2025/11/25-for-25-bolivar-an-american-liberator-by-marie-arana/.