Cahokia: North America's Largest City

United States History

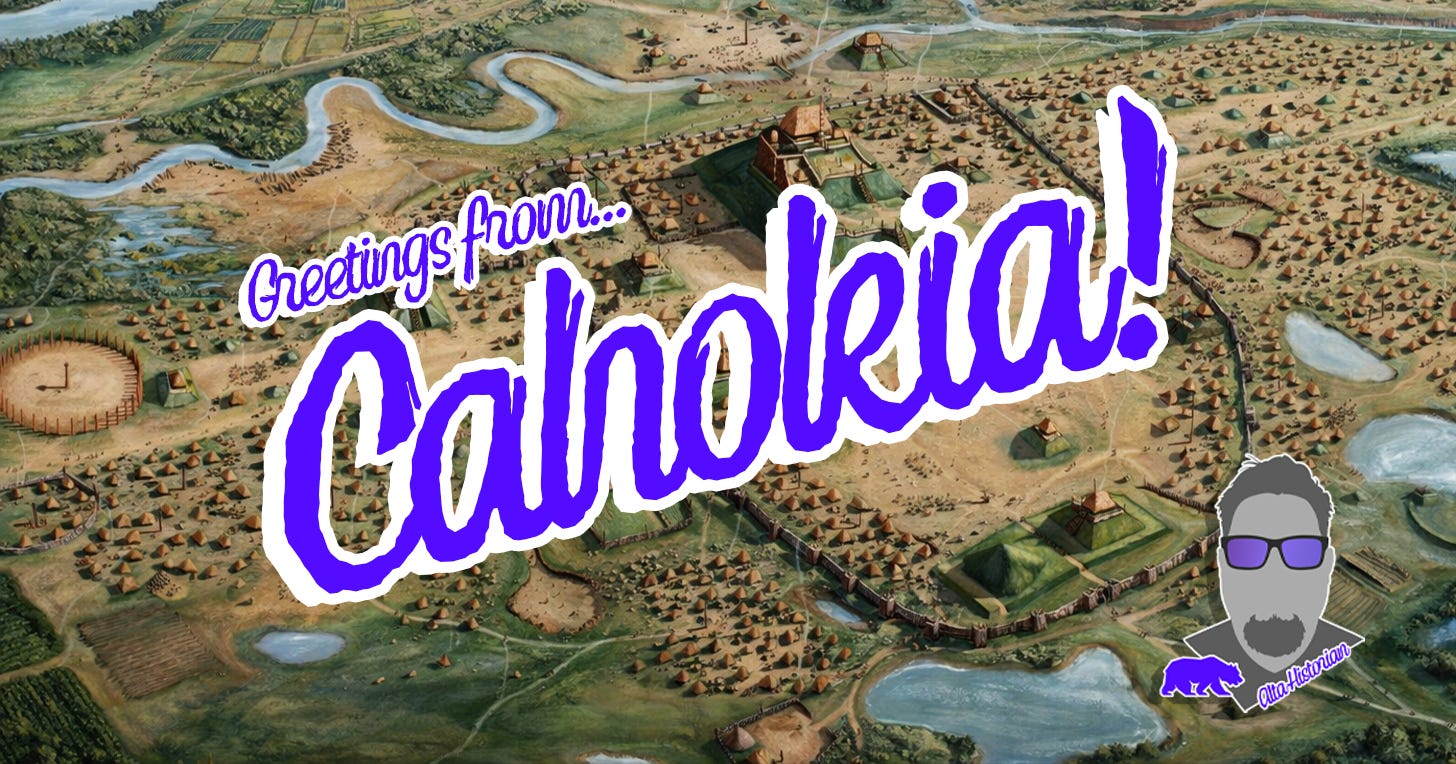

Did you know the biggest city in North America until roughly after the American Revolution was Cahokia (AD 1050 - 1350)? It is one of the most fascinating places in ancient North America, and there has been a great interest in it over the last decade or so among people (like me) interested in this sort of thing. As an undergraduate student in ancient times (the world was in black and white), they were called “mound culture.” In fact, when I went through my old college printouts, one of the articles was on the mound cultures in the Illinois region. In fact, this brings me to the controversial Graham Hancock and his Netflix show, Ancient Apocalypse. You don’t have to believe anything he says, but in episode six, he covers Cahokia, and the visuals are stunning. I imagine the real place was extraordinary — my elementary-age kids loved it.

Let’s go back in time to AD 1200 — Genghis Khan roamed the earth, the Crusaders captured Constantinople in AD 1204, and the Magna Carta was written in AD 1215 (granting British aristocrats the rights of trial by jury and protection against the King’s arbitrary acts). On the other side of the planet, we have some epic historic events going on as well. The Mexica migrated south from Aztlán into Mesoamerica, where they would establish their empire — they’re better known by their academic name, the Aztecs. In the Western portion of North America, where the Mexica are said to have lived before Mexico, a severe drought occurred. Famine. Floods. There is evidence of cannibalism in southwestern Colorado.

They are of Mississippian culture; in fact, Cahokia was the political center of the region between East St. Louis and Collinsville in Southwestern Illinois. The legacy of Cahokia was the complex social, political, and cultural structures inherited by tribes of the North American Southeast—hierarchies of Chiefs, led by a paramount Chief, who oversaw the surrounding villages.

Their influence was in numbers, with estimates ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 people. There are two primary views on Cahokia. One view is that Cahokia acted as a large urban city center where trade, ritual, culture, and politics influenced the entire Mississippian region. The second view is one of a sprawling community with loose-knit, low-density farming spread across a wide swath with Cahokia as a ritual site. In my view, it is the one in the middle: a political and ritual center of power that had major influence in a loose-knit community of low-density farmers.

Around AD 1050, there was a “big bang” in population, where a massive shift in all things Cahokia occurred — social, political, ideological — along with a 500 percent increase in population in just a single generation. Their population boomed around AD 1100 and AD 1200, and was larger than London at the time, second only to the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan. Cahokia was a modern small city, but, like all tribes in North America, it had no writing system. They were organizationally complex, like the Aztec, Maya, and Inca — whom we know more about because of their hieroglyphs or, in the case of the Inca, the writings of the conquistadors.

We do know they practiced astronomy, evidenced by their woodhenge circles (think Stonehenge). One of the better-known woodhenge circles measured 410 feet in diameter, with forty-eight large cedar posts used as a solar calendar for tracking agricultural seasons. But what Cahokia is most famous for is its mounds — there were more than 100 mounds — spread across five square miles, roughly 3,300 acres, spanning larger than many modern towns. Monk’s Mound is the centerpiece, named after the Catholic Trappist monks who lived nearby in the early nineteenth century.

It is believed that these mounds were for the burial of their Great Chiefs. Monk’s Mound is the largest earthen structure in North America, 1,000 feet long, 775 feet wide, covering seventeen acres, standing 100 feet high (ninety-eight to be precise) — roughly the height of a ten-story building. The base is bigger than the Great Pyramids of Egypt. Whoever did this moved roughly twenty-two million cubic feet of earth over an estimated 200 years — enough dirt to fill 300 Olympic-sized swimming pools — and let me remind you, no machines or metals like steel or iron.

Add to Monk’s Mound a platform for — you guessed it — human sacrifice. What are the reasons (hypothosized reasons) for all this? It came down to what it always comes down to in civilizations. Food. Fertility. Rain. Survival. Population expansion was key; more people meant more production, more labor meant more trade, and more trade meant more power. Cahokian priests used myth, the cosmos, and trade to rule over the laboring agricultural producers who made them wealthy, to foster the development of artists, and to obtain fine things from other Mississippian cultures.

Cahokia was politically organized around chiefdoms, a hierarchical, clan-based system that gave leaders both secular and sacred authority. The city’s size and influence suggest that it relied on several lesser chiefdoms under the control of a paramount leader. Social stratification was partly preserved through frequent warfare. War captives were enslaved, which formed a vital part of the economy in the North American Southeast.

Native American slavery was not based on holding people as property. Instead, Native Americans understood the enslaved as people who lacked kinship networks. Slavery, then, was not always a permanent condition. Often, a formerly enslaved person could become a fully integrated member of the community. Adoption or marriage could enable an enslaved person to enter a kinship network and join the community. Slavery and captive trading became a meaningful way for many Native communities to regrow and gain or maintain power.

North American communities were connected by kin, politics, and culture, and sustained by long-distance trading routes. The Mississippi River was an essential trade artery, but the continent’s waterways were vital to transportation and communication. Cahokia became a key trading center partly because of its position near the Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers. These rivers created networks that stretched from the Great Lakes to the American Southeast.

Archaeologists can identify materials, such as seashells, that traveled over 1,000 miles to reach the center of this civilization. At least 3,500 years ago, the community at what is now Poverty Point, Louisiana, had access to copper from present-day Canada and flint from modern-day Indiana. Sheets of mica found at the sacred Serpent Mound site near the Ohio River came from the Allegheny Mountains, and obsidian from nearby earthworks came from Mexico. Turquoise from the Greater Southwest was used at Teotihuacan 1200 years ago.

As with many people who lived in the Woodlands, life and death in Cahokia were linked to the movement of the stars, sun, and moon. Their ceremonial earthwork structures reflect these important structuring forces.

They even had a palisade — a wooden stockade defence wall that enclosed 205 acres around the central area and included eighteen mounds — watchtowers and all. For what purpose? To protect those in power — that’s my theory that seems consistent across all civilizations.

By AD 1300, scholars believe that warfare, internal political instability, and perhaps environmental factors led to decline. As is usually the case with societies in decline, external enemies likely further stoked the flames of Cahokia’s demise. Cahokia leaves no such trail, no such contact, and its decline and disappearance in AD 1400 are equally mysterious, leaving scholarship tied directly to archaeological digs.

Bibliography | Notes

Benson, Larry, Timothy R. Pauketat, and Edward R. Cook. “Cahokia’s Boom and Bust in the Context of Climate Change.” USGS Staff — Published Research 724 (2009). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/724.

Pauketat, Timothy R., and Thomas E. Emerson, eds. Cahokia: Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Schaafsma, Polly. “Documenting Conflict in the Prehistoric Pueblo Southwest.” In North American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence, edited by Richard J. Chacon and Rubén G. Mendoza, 116. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

“Why Did Cahokia, One of the Largest Pre-Hispanic Cities in North America, Collapse?” Smithsonian Magazine, January 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-did-cahokia-one-largest-pre-hispanic-cities-north-america-collapse-180977528/#:~:text=At%20its%20peak,timber%20circles.

The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S. History Textbook. “The New World.” https://www.americanyawp.com/text/01-the-new-world/.