Chinese & Irish Labor in Late 19th Century California

California

In the shadowed dawn of the 1840s, a calamity unfurled across the green hills of Ireland, where the humble potato, the lifeblood of the Irish people, turned to rot beneath a merciless blight. Hunger gnawed at the land, driving a million souls westward across the Atlantic to America—a nation vast and raw, promising refuge yet sparing little mercy to those who bore the stamp of foreign birth. The Irish arrived on these shores threadbare and unlettered, their rough hands and thick brogues met with disdain by the native-born, who saw in them a menace to the workingman’s wage. The Irish spilled their blood for the Union cause during the Civil War—to them, the United States was partly theirs.

So began a journey that would span decades. Their fate would soon involve tangles with other people who had braved an ocean’s expanse in pursuit of fortune or survival. The 1860s brought a new wave to America’s western frontier as the Chinese, strangers from an ancient realm, stepped into California's golden valleys and fog-shrouded cities. They followed in the Irish wake, their numbers swelling until, in San Francisco—that restless port of ambition—they accounted for a fifth of the populace, the Irish nearly their match in strength. The Chinese, too, felt a sense of ownership of the American promise, as they were responsible for the labor that fueled California's Gold Rush and the building of the Transcontinental Railroad that sutured the United States back together after the Civil War.

The Irish and Chinese peoples collided in this cauldron of dreams and dread—not as brethren but as adversaries locked in a fierce contest for place and purpose. The Irish, armed with the ballot’s might, wielded a power denied the Chinese, whose exclusion from citizenship was rooted, as Lee Chew, a Chinese man, starkly noted, in “the jealousy of laboring men of other nationalities—especially the Irish.”

By 1868, a figure of rare mettle emerged amid this gathering storm. Wong Chin Foo, a seventeen-year-old youth, crossed the Pacific from China, his passage secured by an American missionary woman who discerned the promise in his quick, eager mind. He landed first in Washington, D.C., sipping the first draughts of knowledge, then journeyed to Pennsylvania’s Bucknell University.

There, he astonished his professors with a fervor that burned bright. He graduated with honors alongside Yung Wing, among the few Chinese to claim such distinction before the Chinese Educational Mission swelled its ranks in the decade’s waning years. Wong was a man ablaze to rouse China's centuries-old slumber and usher it into the modern age. Unlike Yung Wing, who pursued reform through exalted corridors, Wong gazed at the common folk, believing enlightenment must spring from the soil.

The early 1870s marked a shift for the Irish in California’s rugged tapestry. Historian Joshua Paddison has written of how these immigrants, once the denounced, now took up the mantle of denouncers, turning on the Chinese to prove their own worth—to stake a claim as “patriotic white Christians” in a land that had long questioned their allegiance. The Chinese, who bent their backs in the mines, scrubbed linens in steaming laundries, and drove iron rails through the unforgiving Sierra, were no longer mere laborers in Irish eyes; they were a threat to a hard-won perch in America’s unfolding story.

Yet some voices saw the Chinese through a different lens. Christian missionaries, steadfast in their creed, emerged as their most ardent champions beyond the employers who prized their toil. They contended that these workers did not harm American hands, taking up tasks too harsh or humble for white pride—digging deep into the earth, washing the sweat from others’ clothes, laying tracks across mountains that defied passage.

Wong’s path had wound far by then. After college, he lingered in America, studying its social clubs, benevolent societies, and trade unions with a keen and restless eye. He absorbed their work, charmed those around him, and spoke about them with an elegance that drew notice. He “grasped at the information which was conveyed to him so easily," one admirer recalled, "and discoursed upon it with so much elegance as to attract the favorable attention of those with whom he came in contact.”

In 1870, he returned to China, where he married and found work as an interpreter for the Customs Service in Shanghai and later in Zhenjiang. But he was no mere functionary. Like many of his generation, he chafed under the Qing Dynasty’s corruption and torpor, his spirit restless for change. He traveled the land, a prophet of reform, urging the abolition of opium, adopting American customs, and uplifting the masses through societies he founded.

His words kindled hope but roused the ire of the Qing rulers, who brooked no challenge to their iron sway. Orders came swiftly: dismantle his groups, imprison or execute his followers, and place a $1,500 bounty on his head. For months, he evaded capture, stripped of all he owned, until a Japanese sailor, stirred by his plight, spirited him to Japan. There, an American consul, C. O. Saeppard of Buffalo, secured his passage back to San Francisco.

By 1873, when Wong Chin Foo returned to San Francisco’s shores, the ground beneath such claims had begun to quake. The Chinese were edging into trades whites held dear, their ambition stirring unease among manufacturers who feared competition in labor and mastery itself. The anti-Chinese tide, once a ripple of laws and taxes in the 1850s and ’60s, had swelled into a tempest, its currents lashing at the edges of a fragile coexistence.

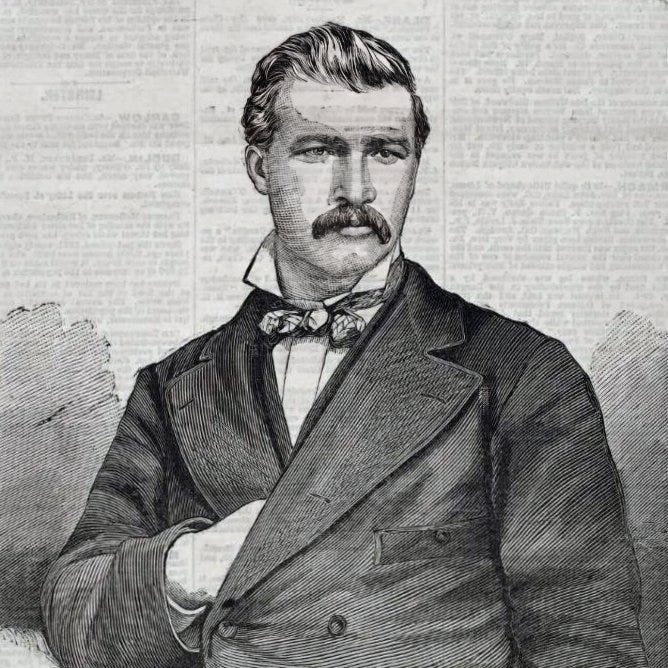

That same year, 1873, saw another titan rise from the dust of San Francisco’s sandlots. Denis Kearney, born in Ireland in 1847, had fled famine as a boy, roaming the seas before dropping anchor in California in 1868. He built a modest trucking business, but at the Lyceum of Self-Culture—a Sunday debating club—he honed a gift for oratory, his brogue thick yet forceful.

By 1877, he emerged as a colossus of the labor movement, founding the Workingmen’s Party of California with a cry that thundered nationwide: “The Chinese Must Go.” Kearney was a paradox—an immigrant with a heavy accent preaching nativism, a demagogue with a laborer’s heart. His party blamed capitalists and Chinese “coolie labor” for strangling wages, a message that struck deep in a state reeling from depression.

The Road to War

In 1876, as a record 22,000 Chinese arrived, fear boiled into fury. That July, an Anti-Coolie club meeting spiraled into a mob torching Chinese laundries. Two days later, over 6,000 men joined a merchants’ militia under William T. Coleman, clashing with rioters who targeted the Pacific Mail Steamship docks—a gateway for Chinese arrivals. Kearney rose amid the chaos, urging workers to arm themselves as equals to the propertied, his voice ringing from sandlots to the gilded streets.

In the charged air of their rivalry, Wong Chin Foo flung a gauntlet at Denis Kearney, daring him to a duel that set the presses ablaze. Ever hungry for a spectacle, reporters pressed close: “What weapons?” they demanded. Wong’s retort came swift and sharp: “Kearney’s choice.” Then, with a glint of defiance, he added, “I offer him chopsticks, Irish potatoes, or guns.”

By February 20, 1875—a date we might imagine as a vantage point—the clash of these two figures framed a nation’s wrestle with its soul. Wong Chin Foo took to the road, delivering over eighty lectures in 1876 alone to “explain away certain misapprehensions” about China. The New York Times captured him in Boston: a young man of twenty-six, clad in a dark suit of fine make, his gold watch and neck-chain his only adornments, speaking fluent English with a grace that defied the crude stereotypes of the day.

Wong Chin Foo was also not afraid to advise on politics, saying,

"Remember the politician who lords it over you today is a coward. When you don’t [have the] vote, they denounce you as a reptile; the moment you appear at the ballot box, you are a brother and are treated to cigars and beers."

He spurned Christianity despite its shadow over his youth, writing to the New York Herald, “I have never slandered or abused while teaching my country’s ways. Is it unfair to ask Christians to hear us, as we hear their missionaries?” His essay “Why Am I a Heathen?” laid bare his doubts—the tangle of sects, each claiming sole truth, bewildered him. He judged faith by its fruits and found his path sufficient. To racist myths of rat-eating, he offered a $500 reward for proof—none came. He used his lectures to “explain away certain misapprehensions concerning his country and people which prevail among Americans.”

Wong stated in a letter he sent to the New York Herald:

“Since I have been in this country teaching the religion and describing the social life and political affairs of my native land, China, I have never slandered, abused and swindled in many [sic] places. I have tried to show the Christians how an honorable Chinamen [sic] looks and talks. You send your missionaries to us and we listen to them. Is it unfair for me to ask them to hear what we have to say? They say that, we, heathens, are to be eternally damned, no matter how honest, moral and sincere we may be. We think Christians will be damned if they behave like very wicked Buddhists.”

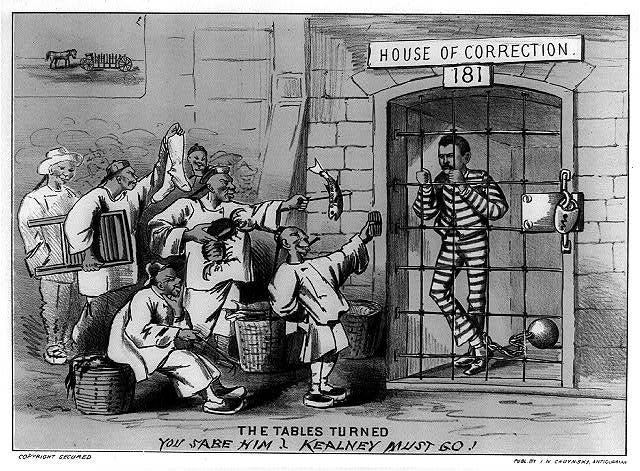

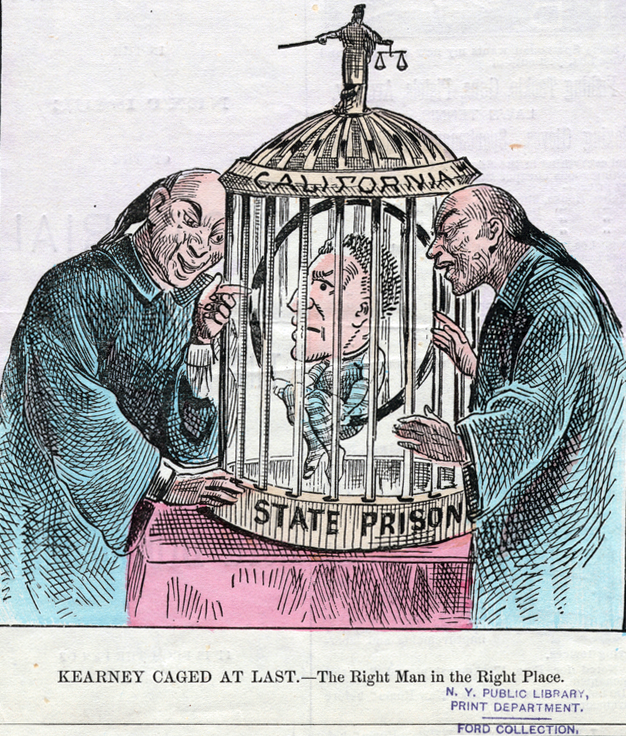

Kearney, meanwhile, rallied the dispossessed with a fervor that shook California’s foundations. The city struck back, banning speeches that incited violence, arresting him only to see him freed after trial, his stature swelling. In 1878, his party seized San Francisco’s voice in a constitutional convention, birthing a charter in 1879 that curbed railroads, eased farmers’ taxes, and lashed at the Chinese—barring their employment by corporations or public works, confining them to districts. It was a vast and tangled document, pleasing no one yet marking Kearney’s triumph.

The Irish and Chinese met as foes in this tumult, the former rising above the latter in America’s pecking order, their attacks sharpest where labor clashed. Violence scarred Chinese lives, fanned by Kearney’s party and echoed in the press. Wong saw misunderstanding as the root of their woes and resolved to bridge it. In 1883, he founded The Chinese American, the first Chinese newspaper in Manhattan, coining a term that defined his fight—not just for the right to be in America, but to be American. He believed in assimilation, not surrender, arguing that those already here deserved a chance to belong.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, renewed in 1892 by the Geary Act, tested his resolve. Wong challenged its denial of citizenship, asking why a Chinese man who embraced American values should be barred. He went so far as to go to Chicago for the famed Columbian Exposition, where he would proclaim,

"We want Illinois, the place that Lincoln called home, to do for the Chinese what the North did for the Negroes."

In 1896, he moved to Chicago, launched Chinese News, and likely met Sun Yat-sen, who declared the city a revolutionary hub. Two years later, he sailed to Hong Kong, made a final journey to Shandong, and died of heart failure in Weihai in 1898.

Wong’s legacy endures—he was a bridge between worlds, a shaper of Chinese-American identity, and a believer in an America that could be. Kearney’s echo faded, but his roar had reshaped a state. Together, they framed a chapter of a nation straining under its promise, liberty bent by fear and want.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lennon, Thomas, Bill D. Moyers, Ruby Yang, Brian Keane, George Gao, Michael Chin, Richard Numeroff, Allan Palmer, Films for the Humanities (Firm), Public Affairs Television (Firm), Thomas Lennon Productions, and WNET (Television station: New York, N.Y.). Becoming American: The Chinese Experience. Princeton, NJ: Films for the Humanities & Sciences, 2003. DVD.

Paddison, Joshua. American Heathens: Religion, Race, and Reconstruction in California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Rawls, James J., and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History. 9th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

Museum of Chinese in America. "Wong Chin Foo." Museum of Chinese in America.” The Independent." Vol. 44. New York: Independent Publications, 1892.

Wong, K. Claiming America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011.