Daughters of the Ages: Women Who Shaped the Ancient World

World Civilizations

History, that vast and sprawling tapestry of human endeavor, often seems a chronicle of men—kings, warriors, and philosophers striding across the stage of time. Yet, woven into its warp and weft are the threads of women whose lives and legacies shaped the ancient world in subtle and seismic ways. From the sun-scorched sands of Egypt to the mist-shrouded courts of Japan, from the bustling streets of Rome to the windswept steppes of Mongolia, women of the ancient world were not mere spectators but architects of events that echo still. Let us step back into their time, hear their voices, and see the world through their eyes.

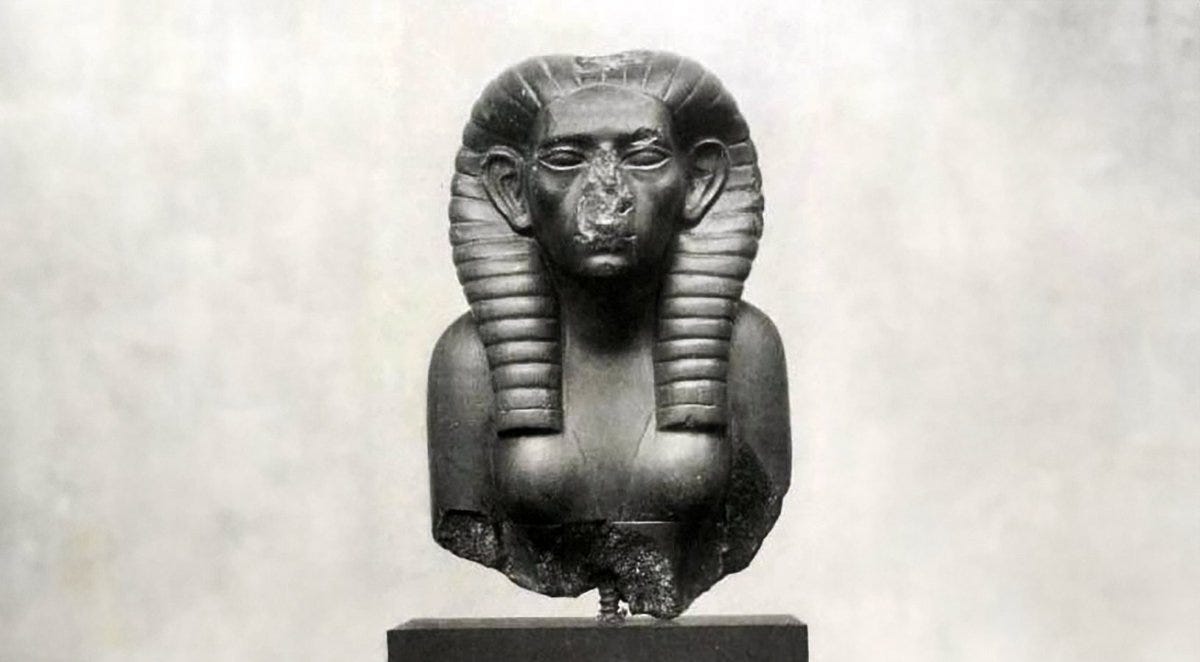

Imagine the banks of the Nile circa 1479 BCE, where the air hums with the rhythm of a river that gives life to a civilization. Here stands Hatshepsut, daughter of Thutmose I, a woman who would not be confined to the shadows of pharaohs’ past. The text tells us of her reign in Egypt’s New Kingdom, when she donned the double crown and declared herself pharaoh—an audacious act in a land where divine kingship was the preserve of men.

She ruled from 1479 to 1458 BCE, her name etched into the annals of history not as a consort but as a sovereign. Her expeditions to Punt, a distant land of incense and gold, brought treasures that enriched Egypt’s coffers and temples. At Abu Simbel, her legacy rises in stone, a testament to a woman who bent tradition to her will and steered her people through a golden age. Hatshepsut’s story is one of defiance and diplomacy, a reminder that power, when wielded with vision, knows no gender.

Now shift your gaze eastward, to the Indus Valley, around 2500 BCE, where the Harappan civilization thrives in orderly cities like Mohenjo-Daro. Among the artifacts unearthed is the “Dancing Girl,” a bronze figurine barely four inches tall yet radiating confidence. The text describes her as a symbol of a society where women may have held sway in cultural or ritual life. She stands, hand on hip, a poised enigma from a world lost to time, suggesting that women here were not just adornments but participants in a sophisticated urban culture. Her silent dance whispers of a balance in Harappan life, where the feminine voice found expression amid the hum of trade and craft.

Travel forward to 1200 BCE, to the chaotic twilight of the Late Bronze Age. The Sea Peoples ravaged the eastern Mediterranean, toppling empires. Yet in Egypt, another woman emerges to steady the helm. Sobekneferu, the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty, steps into history during the Second Intermediate Period. Scholars have noted her as one of the first women to claim the title of pharaoh, reigning briefly around 1800 BCE, a beacon of stability as Hyksos invaders loomed. Her name, linked to the crocodile god Sobek, evokes strength and protection. Although her rule was brief, Sobekneferu’s ascent during a time of crisis highlights how women could rise as linchpins when the world trembled.

Cross the centuries to Rome, 753 BCE, where the city’s founding myth pulses with the courage of women. The text recounts the story of the Sabine women, who were seized by Romulus’s men to populate a fledgling city. But the story pivots on their bravery: these women, caught between captors and kin, intervene to broker peace when war threatens anew. Their pleas halt the clash of swords, forging an alliance that strengthens Rome’s infancy. Here, women are not mere pawns but peacemakers, their voices stitching together a society that would one day rule an empire.

In Rome’s later days, the republic teeters, and women again shape its fate. Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi brothers, emerges in the 2nd century BCE as a force behind reform. The text portrays her as a matriarch whose intellect and resolve fueled the campaigns of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus to redistribute land, thereby challenging the elite. When assassins silenced her sons, Cornelia’s legacy endured—a mother whose influence rippled through a republic on the brink of transformation. Her story is one of quiet power, wielded through family and principle, altering the course of Roman politics.

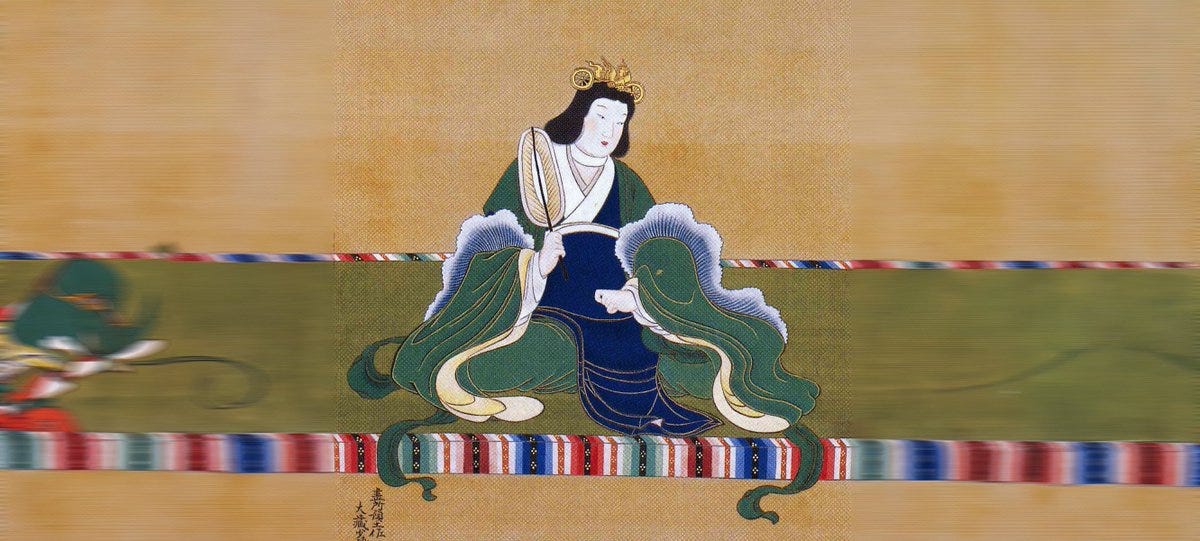

Far to the east, in Japan in the 6th century CE, the Yamato court blossomed under female leadership. Empress Suiko, reigning from 593 to 628 CE, ascended as the first woman recorded in Japanese history to hold the imperial throne. The text highlights her partnership with Prince Shotoku, ushering in the Seventeen Article Constitution—a blueprint for governance rooted in Confucian ideals. Suiko’s reign marks the dawn of the Asuka period, when Buddhism takes root, temples rise, and Japan begins to define itself as a unified state. Her steady hand guided a cultural flowering, proving that women could lead not just in war but in the delicate art of nation-building.

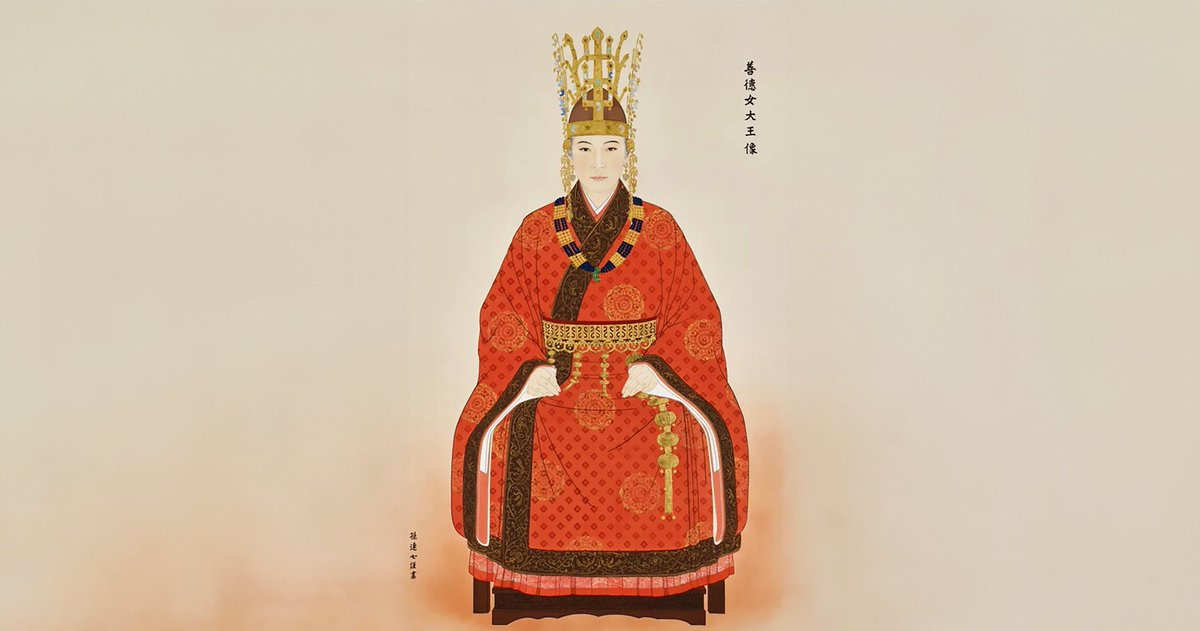

In Korea, the Silla kingdom shines with the brilliance of queens. Seondeok, ruling from 632 to 647 CE, commanded a realm facing Tang China’s might. The text credits her with foresight—building the Seokguram Grotto and fostering Buddhist scholarship. Jindeok and Jinseong's successors, navigating alliances and invasions with acumen, continued this legacy. These women, crowned amid a warrior culture, wielded power that blended diplomacy and devotion, anchoring Silla’s golden age.

Leap to the 7th century CE, to the sands of Arabia, where Khadija bint Khuwaylid stands as a pillar of Islam’s birth. She was Muhammad’s first wife and a wealthy merchant whose support sustained his prophetic mission. In 595 CE, she married him, offering her fortune and faith when he received the revelations of the Quran. Khadija’s death in 619 CE marks a turning point, yet her legacy endures as the “Mother of the Believers,” her courage and resources laying the foundation for a faith that would reshape the world. Without her, the ummah—the Muslim community—might never have coalesced.

Across the Arabian dunes, Aisha, Muhammad’s young widow, emerges as a force in Islam’s early struggles. After he died in 632 CE, she rode into the Battle of the Camel in 656 CE, rallying troops against Ali to shape the caliphate’s future. The text notes her as a scholar of hadith, preserving Muhammad’s teachings for generations. Aisha’s fiery, learned, unyielding voice echoes through the Rashidun era, a testament to women as intellectual and political actors in Islam’s formative years.

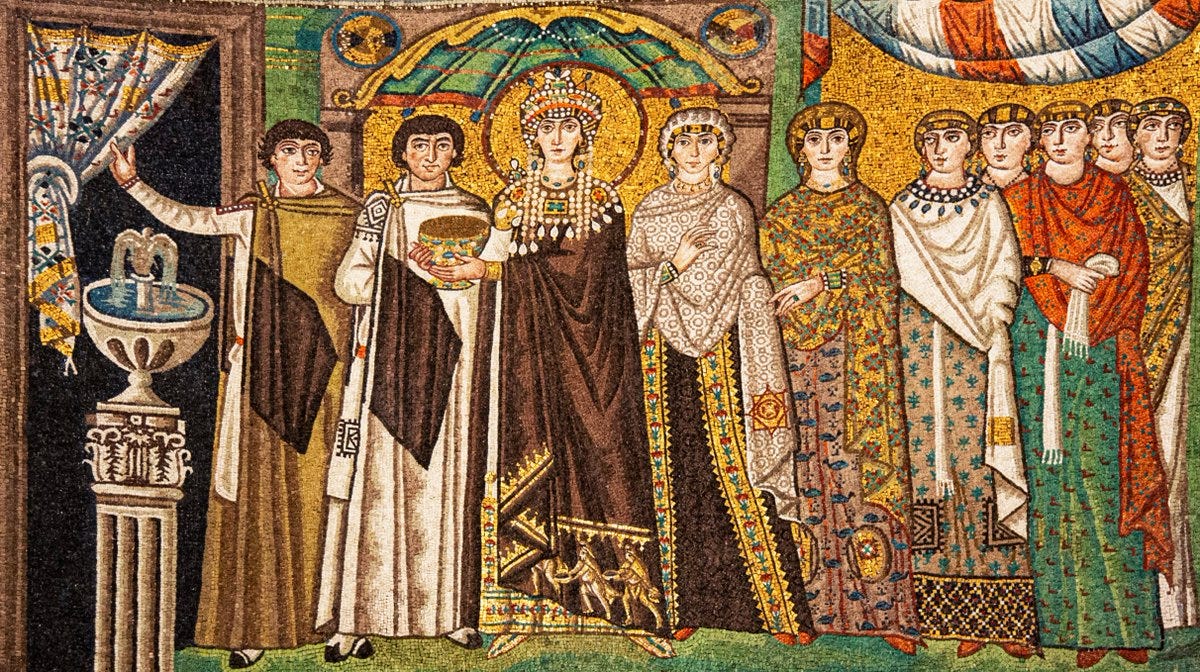

In Constantinople, 527 CE, Theodora rose from humble origins to co-rule the Byzantine Empire with Justinian. Historian Procopius’s Anecdota reveals her as a former actress who becomes empress, her resolve reinforcing Justinian during the Nika riots. When advisors urge flight, Theodora declares, “Purple makes a fine shroud,” persuading him to crush the revolt and save the throne. Her Code of Justinian reforms laws, curbing corruption, and protecting women’s rights. Theodora’s grit and wisdom fortify an empire at its zenith, her influence etched into its marble and mosaics.

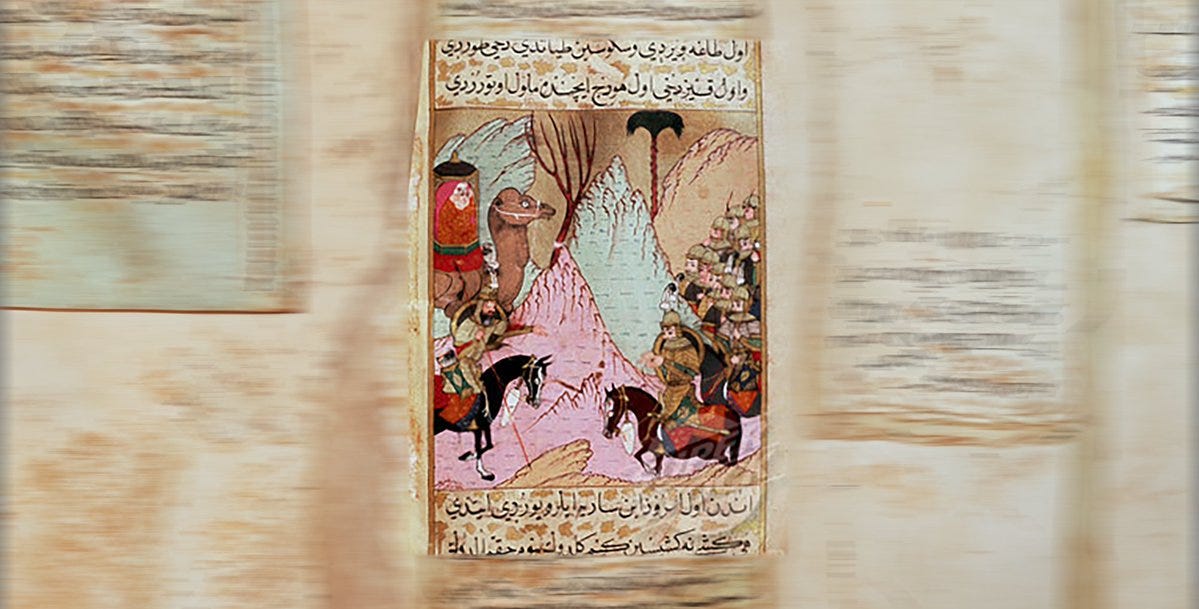

In the 13th century, amid the Mongol storm, Borte, wife of Temujin—later Genghis Khan—stands as his rock. The Secret History of the Mongols recounts her abduction by the Merkits and Temujin’s rescue, cementing their bond. From 1162 to 1227 CE, Borte counseled him as he united the steppes, with her sons—Jochi, Chagatai, Ogedei, and Tolui—extending the empire after his death. In the Baljuna Covenant, she shares his exile, her loyalty forging the “People of the Felt Walls.” Borte’s strength is the sinew of the Pax Mongolica, a peace that spans continents, born from a partnership that defies the chaos of conquest.

These women—Hatshepsut, Sobekneferu, Cornelia, Suiko, Seondeok, Khadija, Aisha, Theodora, Borte, and countless others glimpsed in the text—were not anomalies but vital currents in the river of history. They ruled empires, shaped faiths, brokered peace, and nurtured cultures. Their stories remind us that the ancient world was not solely a man’s domain. Women, with their courage, intellect, and resilience, were indispensable to the events that built our past, their legacies a bridge to the present we must never cease to cross.

These women—Hatshepsut, Sobekneferu, Cornelia, Suiko, Seondeok, Khadija, Aisha, Theodora, Borte, and countless others glimpsed in the text—were not anomalies but vital currents in the river of history. They ruled empires, shaped faiths, brokered peace, and nurtured cultures. Their stories, drawn from the pages of World History, Volume 1, remind us that the ancient world was not solely a man’s domain. Women, with their courage, intellect, and resilience, were indispensable to the events that shaped our past; their legacies are a bridge to the present we must never cease to cross.

Guardians of the New World: Women Who Sustained the Americas

In the vast, untamed expanse of the Americas, where mountains pierce the sky and rivers carve the earth, history unfolds not as a parade of conquerors but as a quiet symphony of survival and creation. Before the sails of Columbus broke the horizon, when the year 1500 drew its line across time, the New World thrived with societies shaped by the hands and hearts of women. From the windswept plains of the north to the emerald highlands of the Andes, women were not mere footnotes but the very sinew of their people—farmers, builders, spiritual guides, and keepers of tradition. Let us journey into their world, a place of ingenuity and endurance, and uncover the stories of those who held the Americas aloft.

Picture the rugged coast of Chile some 11,000 years ago, where the Pacific laps against a shore dotted with the remnants of a forgotten people. At Monte Verde, archaeologists unearth traces of a settlement older than the Clovis hunters who once roamed the plains. In the community of gatherers and fishers, women certainly played a pivotal role. These women, unnamed in the record, were the backbone of a society that defied the ice age’s grip, their knowledge of roots and shellfish sustaining life in a land still waking from the cold. Their legacy is etched in the hearths they tended, a testament to the quiet power of those who nurture when the world is wild.

Move forward to 3000 BCE, to the arid valleys of Peru’s Norte Chico, where the first whispers of civilization rise from the dust. The pyramids and plazas of Caral, a city of stone and adobe, are a marvel of early urban life. Although their names are lost, women here were likely central to this revolution. The Neolithic shift to farming, so vital across the globe, took root in the Americas with crops like squash and beans. Picture a woman in a field near the Supe River, coaxing life from the soil with a digging stick. Her labor feeds a growing populace, and her surplus enables the builders and priests to erect Caral’s monuments. The text notes no kings or warriors here, suggesting a society where women’s agricultural prowess may have held sway, their harvests the currency of a peaceful complexity.

Travel north to Mesoamerica, around 1200 BCE, where the Olmec carved colossal heads from basalt along the Gulf Coast. At San Lorenzo and La Venta, the text portrays a culture rich in ritual and trade. Women, though unsung by name, emerge as vital threads in this tapestry. Imagine a potter, her fingers shaping clay into vessels that hold maize and cacao, staples of Olmec life. Their domestic and ceremonial roles suggest that women were sustainers and mediators between the earthly and the divine. Their crafts—pots, figurines—bear the marks of a spiritual life, perhaps honoring deities like the maize goddess, whose bounty they tended. In a world of jaguar cults and shamanic rites, these women wove the fabric of community, their hands bridging the sacred and the mundane.

By 300 CE, Teotihuacán rose as a metropolis of pyramids and avenues in the highlands of Mexico. The text marvels at the Avenue of the Dead and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, a city of 100,000 souls. Here, women’s importance deepens. Imagine a merchant woman, her back laden with textiles dyed in vibrant hues, trading in the bustling markets. The text notes the city’s vast trade networks, and women likely drove this economy, their weaving and farming fueling exchanges with distant lands. Though there are no names of individuals, it underscores a society of specialization, where women’s roles as producers and spiritual leaders underpinned Teotihuacán’s grandeur.

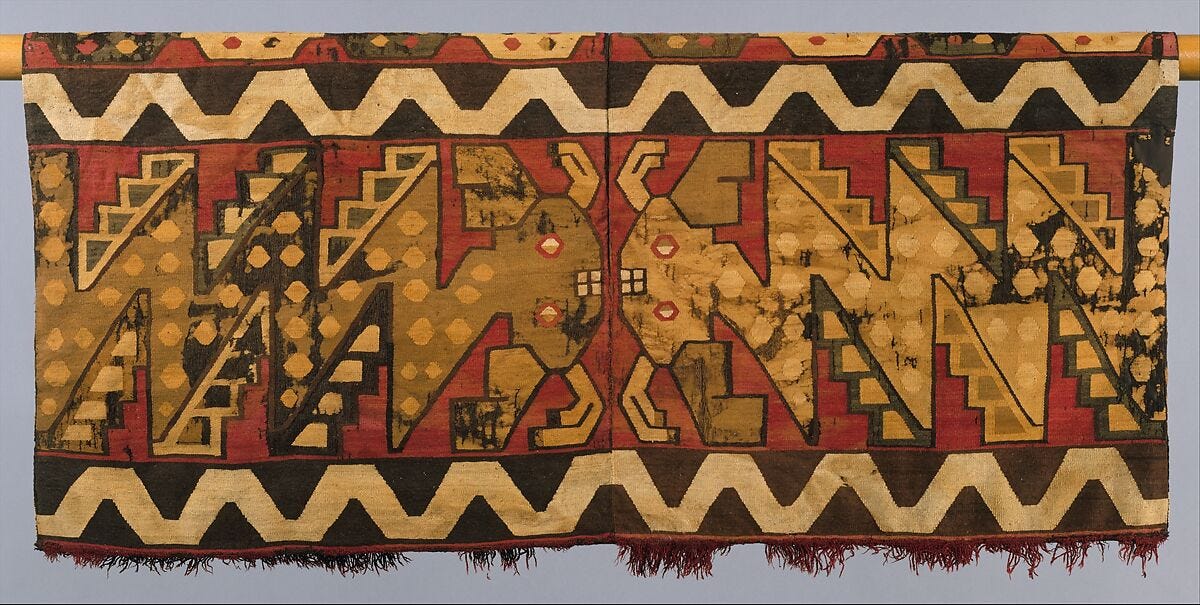

Further south, in the Andes, by 900 CE, the Wari and Tiwanaku cultures flourished amid rugged peaks. The text describes their terraced fields and intricate textiles, highlighting the centrality of women. Envision a Wari woman, her loom alive with alpaca wool, crafting patterns that tell stories of her people. These textiles, prized across the highlands, are more than cloth—they are a language of identity and power. Or see a Tiwanaku farmer, her hands guiding water through stone channels to irrigate quinoa fields. The text credits such ingenuity to these societies’ resilience, and women, as stewards of agriculture and craft, sustained empires that rivaled those of the Old World. Their work was the heartbeat of a civilization that thrived where others might falter.

By 1200 CE, the Mississippi River Valley hums with the energy of the Cahokia mounds. The text refers to it as a “Mississippian tradition,” a network of earthen pyramids that dwarf even the Great Pyramid at Giza in terms of footprint. Women here are the unsung architects of abundance. Imagine a farmer knee-deep in the rich alluvial soil, tending maize, squash, and sunflowers—crops that feed thousands. This agricultural surplus allowed Cahokia’s rise, and women, as cultivators, were its lifeblood. Their labor supports chiefs and ceremonies, their harvests piling high in granaries that signal prosperity. In a land of mound-builders, these women are the foundation, their toil lifting a culture to the sky.

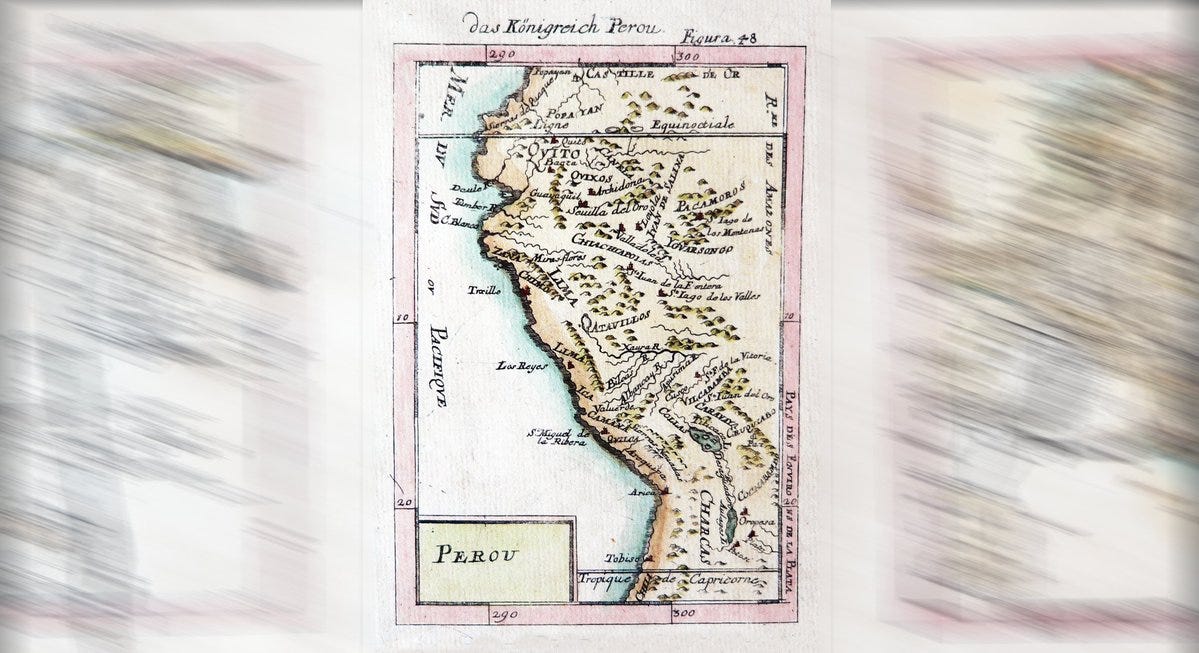

In the 15th century, the Inca knit an empire across the Andes, from Cuzco to Machu Picchu. The text marvels at their roads and quipus—knotted cords recording tribute. Women here were indispensable. Picture an aclla, a “chosen woman,” weaving fine cloth for the Sapa Inca or tending the temple of the sun. These women, selected for skill and sanctity, are the empire’s artisans and priestesses, their work a sacred duty.

Or see a mother in a highland village, teaching her children the knots of the quipu, preserving the Inca’s intricate records. The text notes the Triple Alliance’s reliance on tribute, and women’s contributions—textiles, food, memory—prop up this vast dominion. When Spanish chroniclers like Garcilasco de la Vega later wrote of the Inca, they glimpsed a society where women’s hands held the threads of order.

These women of the New World—gatherers at Monte Verde, farmers at Caral, potters of the Olmec, merchants of Teotihuacán, weavers of the Wari, cultivators of Cahokia, and acllas of the Inca—were not mere bystanders. Though sparing with names, the historical record reveals their fingerprints across the Americas. They tamed the wild, fed the multitudes, wove the sacred, and bound communities with their skill. Before 1500, in a world untouched by European steel, they were the quiet giants whose labor and wisdom built societies as enduring as the stone they shaped. Theirs is a legacy of resilience, a song of the New World sung in the voices of its daughters, echoing through the ages to remind us of the strength that lies in those who sustain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kordas, Ann, Ryan J. Lynch, Brooke Nelson, and Julie Tatlock. World History, Volume 1: to 1500. Houston: OpenStax, Rice University, 2023.