It was November 3, 2004, in Moon Township, Pennsylvania. I was a student at Robert Morris University, a football player, and a Social Sciences major. I was crossing campus on crutches, through the snow, making my way to Massey Hall. Levi’s. Black Doc Martens. Brown leather jacket. James Carville was speaking, and I always tried to get tickets to events like that.

Usually, I would have been at football practice. But I had broken my leg in September (a tibial plateau fracture, if you’re curious). The injury effectively ended my career. My spirits were crushed. To make matters worse, I fell more than once while navigating campus. The handicap door buttons didn’t work, and I kept losing my balance in the pass-through buildings. Eventually, I spoke to the university president. The doors were fixed.

Speaking to a university president? Never could I have imagined that growing up.

I grew up in California’s San Gabriel Valley. From what I remember, Hispanic neighborhoods were politically navy blue. I’m not even sure what that meant at the time. I remember seeing Grace Napolitano's signs everywhere as a high school kid and asking, “What kind of name is that?”

As an older Millennial, my memories feel like a history book with a strange soundtrack. I vaguely remember the fall of the Berlin Wall. I definitely remember David Hasselhoff, though I knew him as Michael from Knight Rider, singing and speaking German while everyone cheered. I really thought his name was Michael. I was sitting on the living room floor with my twin brother, staring up at our big-screen TV. It was New Year’s Eve, 1989. I looked it up. That part checked out.

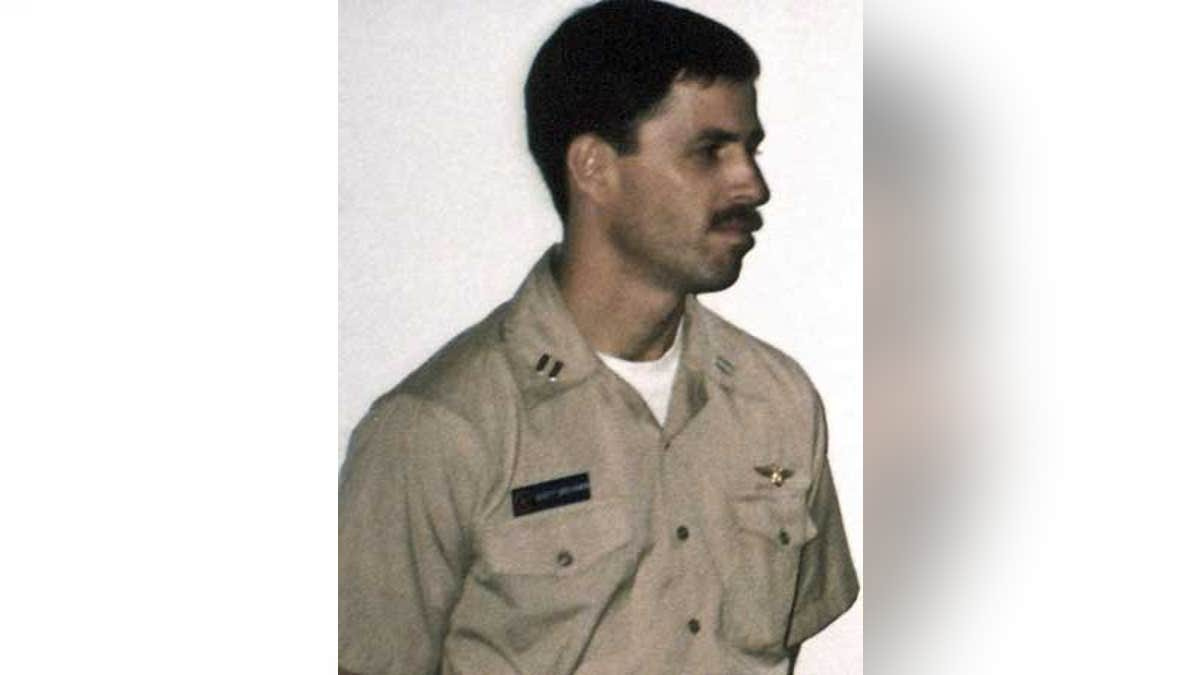

I remember the first Iraq War more clearly. I remember watching CNN, seeing American fighter jets on the screen, and the image of the first pilot killed in the war. If I recall correctly, he had a mustache and light brown hair parted to the side. Or maybe that’s my imagination. As I tell my students now, look it up.

I did. Lt. Cmdr. Scott Speicher. Shot down January 17, 1991. I remember wondering if his family was okay. I still see his face. Looking it up felt like walking back into the past. I can’t be certain this is precisely how it went, but in my memory, this face below was the one I remember. I was seven years old. Moments like that made me a patriotic kid.

I remember the Rodney King beating and the Los Angeles riots. I watched Magic Johnson tell the world he was HIV positive. I remember memorizing the fifty states and winning a trip to McDonald’s for writing the best essay. I visited Mrs. Harvey’s husband after lunch at the Navy recruiting office. I felt like a king.

The following year, I sang along to a record of America the Beautiful in Mrs. Moon’s class. Her son was in the Navy. Super patriotic.

I remember the O.J. Simpson trial and The Simpsons. Mr. Near, a young, hip seventh-grade social studies teacher, had us watch O.J.’s trial in class and said, “This will be history one day.” He was right. I remember the Menendez brothers. The baseball strike. I remember knowing deep in my soul that I was not a fan of MASH*.

My only real exposure to Vietnam was visiting the traveling Vietnam Memorial at City Hall in kindergarten and scratching the name of my teacher, Mrs. Montoya’s husband. She had a pet pig. I remember her crying that day.

I remember seeing Nirvana’s “Teen Spirit” video for the first time and thinking, whoa.

I remember my dad letting us stay up late to watch The Arsenio Hall Show because a young governor from Arkansas was on that night, playing the saxophone. My Uncle Pancho played the sax. So did my aunt. Clinton seemed cool, just like Uncle Pancho. My aunt—she’s so Democrat her cat is a Democrat. I always ask if the cat is dead. She gives me the look.

By middle school, it was Clinton versus Bob Dole. Then Bush versus Gore. Hanging chads. And, of course, Bush’s brother just happened to be the governor of the state in question. Of course, he was going to win. Even then, Gore didn’t seem cool, beyond being Tommy Lee Jones’ college roommate. Now, if it had been that Tommy Lee, maybe perceptions would have shifted. I wasn’t old enough to vote anyway.

Then came college.

Then came 9/11.

I remember watching the second plane hit the tower. After the first, I remember thinking, what an accident. The second plane hit, and the world changed. Yankees and Mets in the World Series. FDNY hats on every corner. American flags were everywhere. Moments like that made me patriotic.

I registered to vote on campus. If memory serves, I registered as a Republican—same as Bush. At the time, Republicans were framed as fiscally responsible, conservative with money, and rich. None of my teachers spoke kindly of Republicans. Many of those same teachers didn’t think much of me either, which probably pushed me further in that direction. Rebel, rebel.

Meanwhile, I was listening to Rage Against the Machine, who played outside the Staples Center during the Republican National Convention in 2000. My friends went, I think they ditched school. I had football practice.

By the time I got to Robert Morris University, I missed Henry Kissinger while stuck in my dorm room recovering. Bill Clinton came to Pittsburgh. Big deal. So did George W. Bush. My buddy KP and I went to watch Air Force One land. KP swore the lights on the towers flashed differently. He was right. I looked it up. It had to be December 2003 or April 2004. It was cold. I’m leaning toward April. Bush was with Santorum. KP loved Santorum.

It was a fun time in politics. Or at least an interesting one.

I stumbled into events supporting Santorum mostly because his office had student internships, and I was new to campus. Being from California, I didn’t know many people yet. I went to see any speaker I could—though most spoke during football practice.

Robert Morris University is known for punching above its weight. Great speakers. Great football coaches. Joe Walton. Dan Radakovich. John Banaszak.

One day in September 2003, on my way to practice, I literally ran into Rudy Giuliani in the campus bookstore. He waved off his bodyguard and joked, “I don’t know if you’d stop him anyway.” I was 6’2” and never turned down a fight. He might’ve been right.

At that moment, he was America’s mayor. He asked about my major. He liked my football shirt, asked if he could get one, they were issued not bought. He asked where I was from. California, I said. He said he collected a memento from every college he visited. That was it.

Actually, I told him I wanted to be a dirty, rotten, scoundrel politician like him. Just kidding. That’s a joke.

I also remember the snipers on the rooftops. That kind of thing sticks with you.

That night, I told my parents. It felt like something, but I didn’t know what.

I wasn’t the most memorable interaction that day. That honor went to Darin DiNapoli, who asked Giuliani about crowd-surfing with his band. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette covered it. My name made the same paper, too—just not for anything that cool.

That same year, we traveled through New York for a game, and my future roommate Kevin pointed to the skyline and said, “That’s where the Twin Towers used to be.” Seeing the void was surreal. Later, we saw the Statue of Liberty. I remember staring at it while eating a boxed lunch in the parking lot after our game at St. Peter’s College—the Peacocks.

Later that year, my phone rang during Mr. Donaldson’s history class. Nobody ever called me—we knocked on windows where I was and where I was from. It was my mom telling me Arnold Schwarzenegger had been elected governor of California. My idol. My brother got me a campaign poster at his rally in Bakersfield. It still sits in my office. I told my professor after class. He smiled and said that was good.

Now, a year later, here I was—on crutches, in Massey Hall, waiting to see James Carville.

Packed house. Great seat. I went alone. The crowd went wild when he walked out. Thin. Clean-shaven head. Sharp suit. I had never seen someone dressed like that in real life.

He stood stage left—if memory serves—and went off. Highs. Lows. Punchlines. Big gestures. Charisma. He wasn’t saying much that resonated with me, but I couldn’t look away.

My only thought was this: I need to learn to speak like this.

Bold. Confident. Loud.

Even after that performance, my economic conservatism didn’t shift. That wasn’t Carville’s fault. Or Clinton’s. Maybe Gore’s a little. The real influence came earlier—from Mr. Donaldson, a part-time professor who introduced me to Locke, Hobbes, Machiavelli, and, most importantly, Thomas Jefferson.

That was just a seed.

Jefferson’s republicanism, the mix of minimalism, restraint, and political tact, became my anchor. Many Republicans point to Lincoln. Others to Reagan. I studied Teddy Roosevelt for years. But no one shaped my thinking more than Jefferson. Read him. Read his letters. Throw in Andrew Jackson for fun.

Politics didn’t find me all at once.

It found me in pieces.

This concludes Part I.