Lucile Hooper & the Creation of the Cahuilla

California History

As you can probably imagine, I love history — but something that piques my fascination is reading about the historians who documented history. Perhaps I see their lives in mine, so to speak. And in the Origin of the Cahuilla, we use Lucile Hooper’s The Cahuilla Indians, which she produced in 1920. In this case, being a woman in Anthropology (or History) was not easy in the 1920s! Let’s look at this historical figure who documented history.

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, on December 23rd of 1892, Hooper lived in a household shaped by professional discipline and intellectual seriousness — her father was a physician, and learning was treated not as an ornament but as an obligation. This built-in persistence would help her when, at the age of twelve, Hooper lost her left arm above the elbow in a horse riding accident. She persisted — learning to swim, dance, and even ride again. Her disability became but a footnote in her story.

Hooper pursued higher education at a time when many women simply attended college as a prelude to marriage. She earned a Master’s degree in Anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, no small task. Her pioneering work culminated in the completion of her thesis, during which she traveled to Southern California alone to live among the Cahuilla Indians. Hooper immersed herself in their world, and from this wonderful work comes our reading today.

For a young woman in the early twentieth century, such an undertaking was not simply uncommon — it was audacious. Her thesis, a serious study of Cahuilla life and culture, was published and remains available in library archives, a quiet testament to fieldwork conducted before “fieldwork” had become fashionable.

In 1918, amid the global devastation of the Spanish Flu epidemic, Lucile nearly died. Survival in that year carried its own moral weight; it marked a generation that had learned how contingent the future could be.

While at Berkeley, Lucile met Arthur Thornton LaPrade. They married on August 31, 1918, in Pasadena, California, and together raised four children. The marriage joined two lives formed by discipline and endurance — hers shaped by loss and learning, his by shared intellectual ground — and from it emerged a family sustained by resolve rather than sentimentality. She passed in 1983 — a fulfilled life of intellectual pursuit and familial love.

Note: I have made minor grammatical adjustments to improve readability. I have also added some graphic novel pages for fun (and perhaps better comprehension).

ORIGIN

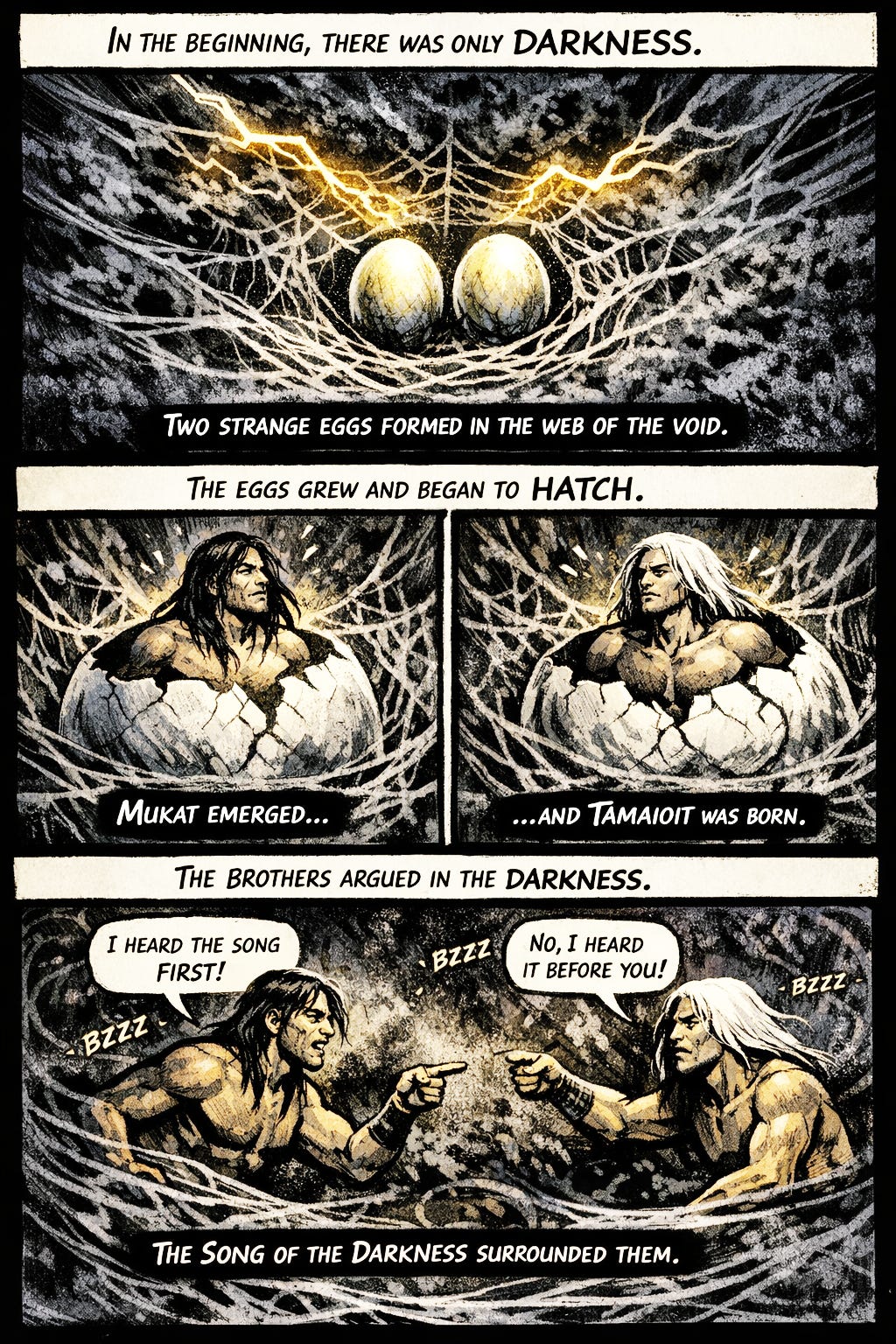

In the beginning, there was no earth or sky or anything or anybody; only a dense darkness in space. This darkness seemed alive. Something like lightning seemed to pass through it and meet each other once in a while. Two substances that looked like the white of an egg came from these lightnings. They lay side by side in the stomach of the darkness, which resembled a spider web. These substances disappeared. They were then produced again, and again they disappeared. This was called the miscarriage of the darkness. The third time they appeared, they remained, hanging there in this web in the darkness.

The substances began to grow and soon were two very large eggs. When they began to hatch, they broke at the top first. Two heads came out, then shoulders, hips, knees, ankles, toes; then the shell was all gone. Two boys had emerged: Mukat and Tamaioit. They were grown men from the first, and could talk right away. As they lay there, both heard a noise like a bee buzzing at the same time. It was the song of their mother, Darkness.

ATTEMPT TO CREATE LIGHT & MAKING TOBACCO

Mukat said he was the first to hear the song, but Tamaioit declared that he was. They argued about this because the first one to hear it would be considered the older, and each desired this honor.

As they lay there, they seemed to be old enough to think. Mukat suggested that they make light so that they might see. Tamaioit said, “You think you are older, now carry out your ideas.”

They began creating things. Mukat reached into his mouth and took from his heart: (1) a cricket, Shilim shilim; (2) Papavonot, another insect; (3) a black and white lizard, Takmeyatineyawet; (4) a person, Whatwhatwet.

Mukat and Tamaioit decided to turn all these new creatures loose and let them drive away the darkness. Since Mukat had made them, they had almost as much power as he. Lizard tried to swallow the darkness, but was unsuccessful. Finally, all of them together managed to drive away the darkness in the east, and then a little light appeared. But when they returned to Mukat and Tamaioit, the darkness they had driven away rushed back, and they could not drive it away again.

Mukat and Tamaioit then said they should have something to smoke to remove the darkness, just as medicine men smoke now to remove disease.

They therefore planned to make tobacco. Mukat took black tobacco from his heart, and Tamaioit brought forth a lighter colored tobacco. Next, they needed some way to smoke it, so they each brought forth another substance from the heart. Mukat’s was dark, Tamaioit’s was light. With this, they made pipes. There were no holes in these pipes, so each pulled out a whisker and pierced a hole in the pipe. Mukat then took a coal of fire from his heart to light the tobacco with. Now they were ready to smoke. Mukat filled his pipe, held it up, and inhaled.

He then decided to play a trick on Tamaioit, so he handed his pipe to him and said, “I am holding it up high,” but he held it low, and in the dark, Tamaioit could not see it. However, Tamaioit was always suspicious of Mukat, so he reached low instead of high, as Mukat expected him to do, and seized the pipe. Tamaioit then got his pipe ready to smoke, held it out to Mukat and said, “I am holding it low,” and really held it that way. Mukat, thinking the same trick was being played on him, reached high and, of course, missed it. Therefore, Tamaioit claimed he was wiser because he could not be fooled.

CREATION OF THE EARTH & PEOPLE

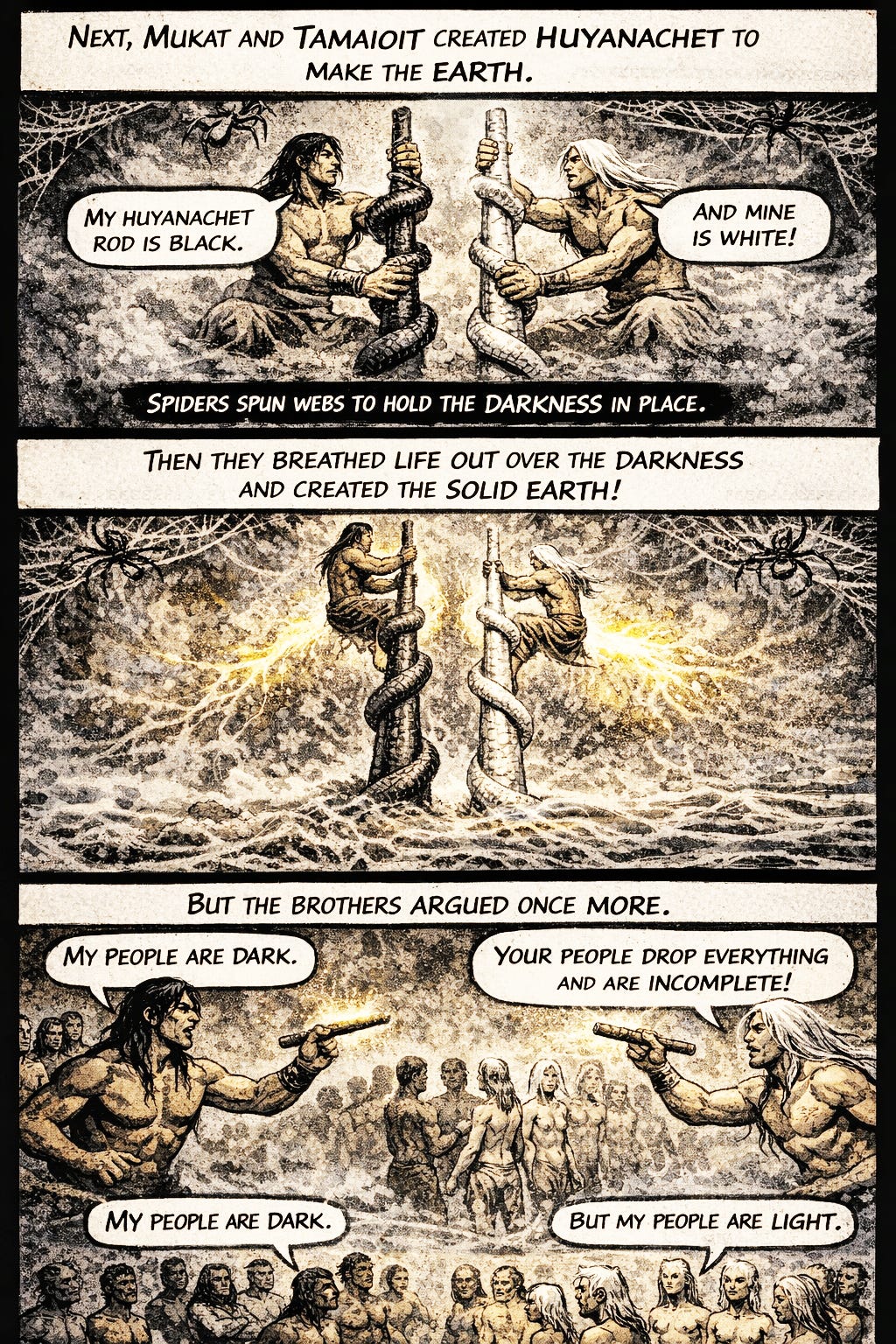

They next took a substance from their hearts to make a huyanachet (rod). As usual, Mukat made a black one and Tamaioit a white one. These were to be the roots of the earth.

When they tried to stand, they found they needed support, so they made snakes to twine around them. Even this was not enough, so they made spiders that crawled to the top of the rods and made a web from there to the corners of the darkness.

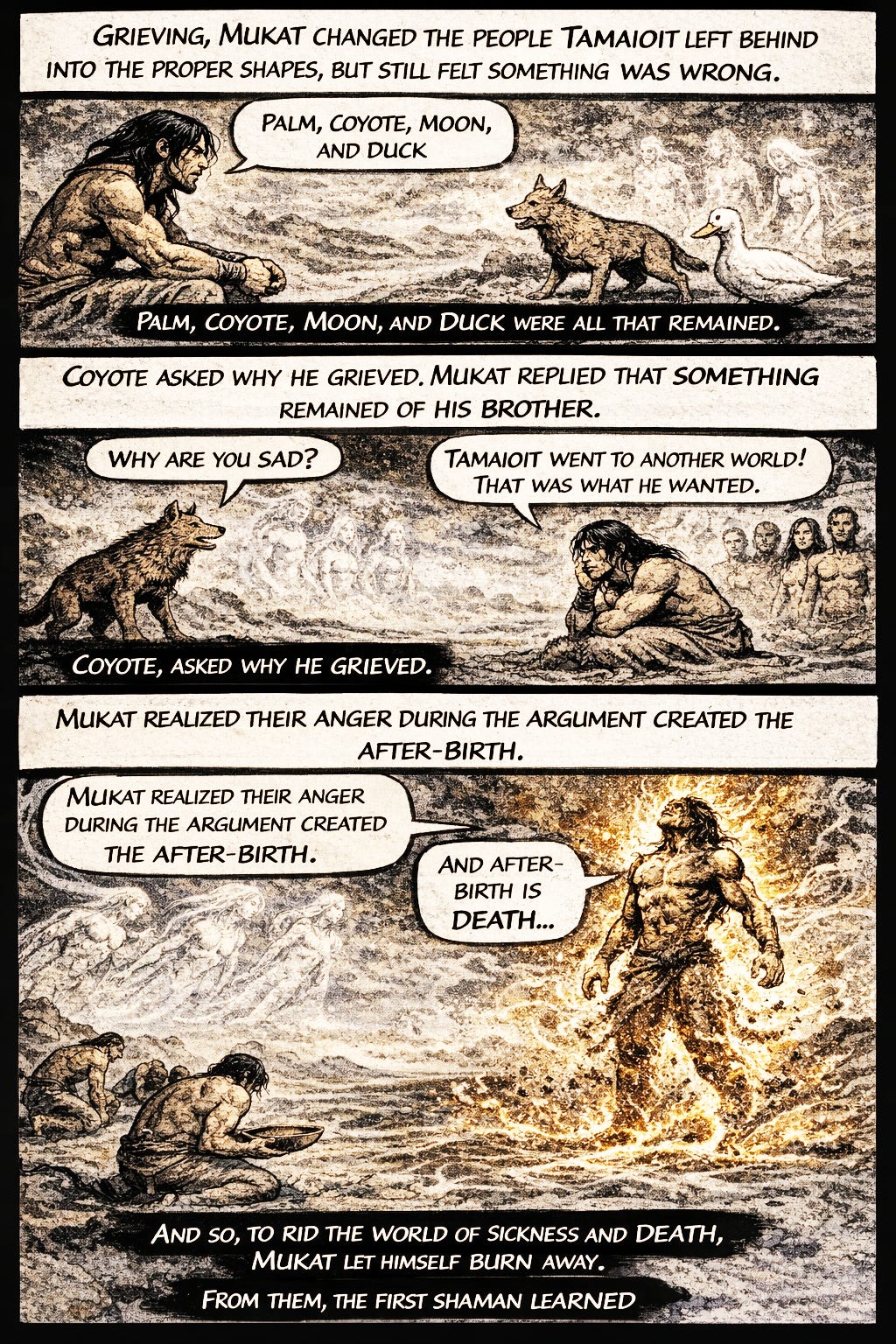

The huyanachet were then firm. Mukat and Tamaioit climbed up to the top but had to rest several times. When they reached the top, though it was dark, they could see that something like a mist or smoke was rising up from below. Mukat asked Tamaioit what it was, and he answered, “I have always told you that I am the older, but you say you are. How does it happen you do not know that that is our after-birth coming up behind us, and that it causes all sickness and disease.” Mukat then made a song about it; he never seemed to know things first, but he always thought about creating things before Tamaioit did.

While up on the top, Mukat now thought about creating Earth, so he suggested it to Tamaioit. Tamaioit said, “I have always told you I am the older, but you say you are. So just go ahead with your ideas and don’t consult me.” But he consented to help. Mukat sang his song, then both shook all over, and soon a substance poured from their mouths, ran down the poles, and spread everywhere, even reaching the top of the huyanachet.

This substance was very soft at first; to make it solid, they created whirlwinds to dry it and a brush to firm it. They also made many kinds of insects of various sizes for this same purpose. Many of these insects have since then been used by shamans, who take them and let them bite a person who has a pain, and that person is then cured. The whirlwinds they took were of two kinds: teniosha, the worst, and tukiaiel. These whirlwinds live in ant holes, and when a fire is placed in these holes, the whirlwinds whistle in their anger. They are dangerous, for they often steal souls.

After Mukat and Tamaioit made the earth, they made the ocean to hold the earth in one place. They made creatures and weeds to live in the ocean. The sky was made of metal so that it would be strong enough to stay up high and not fall. In the sky, they put stars to make more light.

Now that the earth was solid and ready to walk upon, Mukat asked what they should do next. Tamaioit said, “You say you are older, so go ahead with your ideas.” Mukat said that he thought it was now time to create people, for they needed someone to talk to and play with.

This they did, Mukat making dark people and Tamaioit light people. As he made them, Tamaioit placed his people in a circle around him. When his circle was nearly completed, Mukat had only enough to go halfway around him. Mukat wondered how Tamaioit could make them so fast, so he made Sun in order to see.

The Sun was too hot to hold and slipped away from him and went east, so there was not very much light yet.

Mukat told Tamaioit about Sun's escape and asked him what they should do about it. Tamaioit said, “You insist that you are older than I — if you are, it is strange that you have to ask me what to do all the time.” However, he consented to help, and the two of them created Moon. Moon was a woman and was very bright and beautiful and white.

After she was created, Mukat could see Tamaioit’s people, for there was more light. He did not like the people at all.

Tamaioit’s people were exactly alike on both sides. They had faces on both sides, toes pointing in both directions, breasts both in front and in back. All the fingers and toes were webbed.

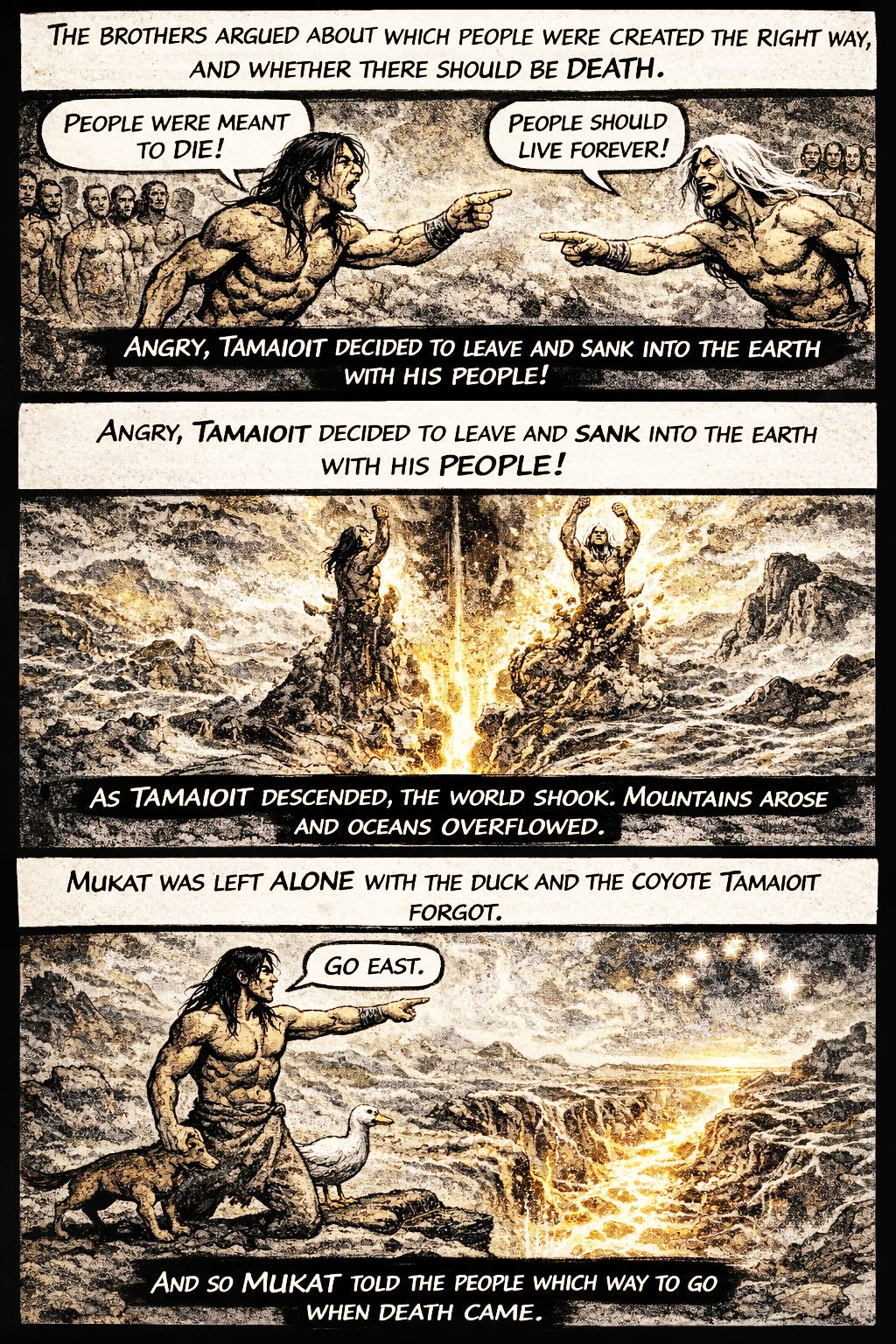

Mukat said, “No wonder you could make them so fast, they don’t look good at all. You should make them right: look at mine.” A quarrel followed. Tamaioit said, “My people do not have to turn around to see behind them, nor will mine drop things through their fingers as yours will.” Mukat said, “Mine can close their fingers when they wish to hold things.” Tamaioit said that people should live always, or, if there was death, the person should return to life the next day and be young, or else people should remain young always.

Mukat said it would be better not to die, for the world would get overcrowded and there would not be enough food for all. Tamaioit said they could make both more food and more room to live in. Mukat said it was intended that people should die, for after-birth’s blood was meant to bring disease into the world and thus cause death.

They then said they must create doctors to care for the people. They had created an old wood far north and a mermaid under the water. The wood and the mermaid were chosen to give the doctors power. They created a very short man in the north, Keketumnamtum, who was to be a medicine man and give power to the people through their dreams of the North Wind or Rain. After obtaining this power, they would be able to create wind or rain.

This world is a man. Rain was created and sent to the sky. Rain is a man who makes things grow. North Wind is a man who makes things dry up.

Mukat and Tamaioit tried to decide when things should grow and ripen. First, they said it should take fifty menyil (moons), but later they decided that it should be four menyil, and thus it is today.

They quarreled continually about which people had been made the proper way, and as to whether there should be death or not. Finally, Tamaioit got angry and said that, since his suggestions here seemed to amount to nothing, he would go to another world and take his people with him. He said that, if he went down into the ground, the world would turn over; Mukat said he would prevent that.

Tamaioit then sang his song and sank into the earth, taking all his people with him. In his hurry, he forgot Palm, Coyote, Duck, and Moon. Earth and Sky wanted to follow him, but Mukat knelt on the earth and held his hand up to the sky; by doing so, he prevented them from going. There are now five stars in the sky where his fingers rested.

As Tamaioit went into the ground, there was a tremendous rumbling and earthquake. Mountains arose at this time, and the water in the ocean shook so that it overflowed and caused the rivers and streams we now have. The sky became bent and curved. Because of this, the sun seems to stop at noon when it reaches its highest point. While the sun is lighting up the world for us here, it is dark in the world below; when we see it go over the horizon in the evening, it is beginning to get light there and grow dark here.

Mukat took the people Tamaioit forgot and made them into the right shape, but he forgot the duck’s feet; so they are still webbed.

While Mukat and Tamaioit were creating people, Mukat created a place in the east for the spirits of the dead to go to. He pulled out a whisker and pointed it east. This made a road. At the end of this road was a gate. Montakwet, a man who never dies, guards this gate. Just beyond this gate are two large hills that constantly move apart and then come together. As they move apart, an opening is left through which the spirits may enter.

If the spirit has been wicked during its lifetime, it is caught between these moving hills and crushed; it then becomes a rock, bat, or butterfly. If it has lived a good life, it passes through this opening safely and enters the regions beyond, known as Telmekish.

Because this road over which the spirits travel is toward the east, one must never lie with one’s head in that direction while sleeping; death might result. It is well enough to do this when old, for an old person can live only a short while longer anyway.

The story continues with sections on Mukat's life and his people, his death, and the conclusion, but the core creation narrative ends with the departure of Tamaioit and the establishment of the afterlife road. The latter parts describe post-creation events, cultural practices, and the mourning fiesta.

The only previously recorded information on the Cahuilla origin story is the outline given by E. W. Gifford, Univ. Calif. Publ. Am. Arch. Ethn., XIV, 188, 189, 1918.

T. T. Waterman has summarized and analyzed most of the literature on the origin myths of the southern California Indians in the American Anthropologist, n.s., XI, 41-55, 1909.

Note: The text is from “The Cahuilla Indians” by Lucile Hooper, 1920, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 16.