Naming California

California History

The name itself arrives freighted with myth, rumor, and print — not as a geographic certainty, but as an idea already half-formed in the European imagination before it ever touched the Pacific Coast.

During Hernán Cortés’ absence from central Mexico, the arrival of Nuño de Guzmán on the western frontier helped propel Spanish exploration northward along the coast. By June 5, 1530, Guzmán had advanced as far north as the Río Grande in present-day Nayarit. A week later, he reached the Río San Pedro near Tuxpan. These movements were not guided solely by reconnaissance or imperial logic. Guzmán, like many of his contemporaries, was deeply susceptible to the rumors and mythology circulating among the conquistadors.

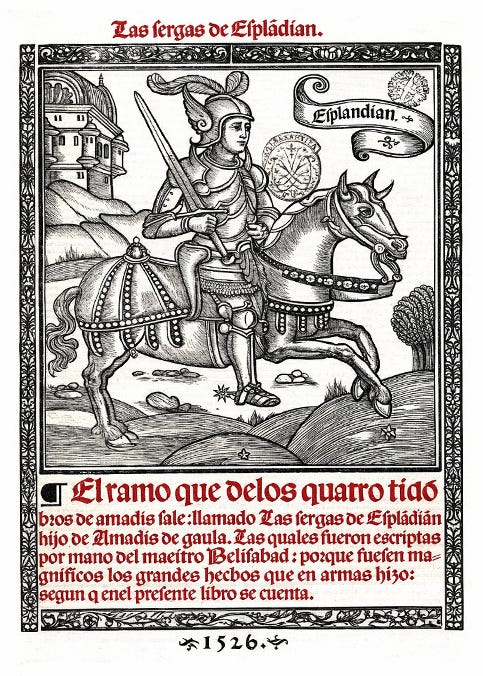

He fully expected to find the kingdom of the Amazons just north of the Río San Pedro, near Aztlán. That expectation — extraordinary as it now seems — was likely shaped by a work of popular literature rather than any indigenous report or geographical intelligence. Garci Ordóñez de Montalvo’s Las Sergas de Esplandián (The Exploits of Esplandián), first printed in 1510, had already planted the name “California” firmly in the European imagination. In De Montalvo’s romance, the name appears in print for the first time. The book’s immense popularity, sustained through numerous printings throughout the sixteenth century, ensured that any reasonably educated Spaniard would have known it well.

The description appears in multiple passages, but one of the most frequently cited occurs in chapter 157:

Know that, on the right hand of the Indies, very near to the Terrestrial Paradise, there is an island called California, which was peopled with black women, without any men among them. because they were accustomed to live after the fashion of Amazons . . . In this island called California are many Griffins, on account of the great savageness of the country and the immense quantity of the wild game there . . . Now, in the time that these great men of the Pagans sailed (against Constantinople) with those great fleets of which I have told you, there reigned in this land of California a Queen, large of body, very beautiful, in the prime of her years….

Here, California enters history not as land, but rather, as legend — an island near Paradise, ruled by a queen, defended by griffins, and inhabited by warrior women. The name did not wait for maps. It preceded them. And many would argue, California has lived up to its name, though not quite as fantastical as a Wonder Woman (2017) scene.

The term “California” appears again, this time outside the realm of fiction, in the memoirs of Captain Bernal Díaz del Castillo. He wrote, “Cortés again set sail from Santa Cruz and discovered the coast of California.” Together with De Montalvo’s romance, these references constitute the earliest surviving documentation of the name. Yet it seems likely that “California” was already in general circulation among the conquistadors before 1530, spoken aloud long before it was fixed in ink.

The origin of the name has since become a subject of sustained dispute. Over time, proposed explanations have ranged from the merely speculative to the extravagantly implausible. One theory attempted to derive the word from Latin — calida fornax, “hot oven” — a construction as clever as it is unsupported. There is no recorded instance of Cortés assigning names through Latin etymology.

Another hypothesis suggested that California derived from an Indigenous word meaning “a high hill,” but its proponents were unable to demonstrate such a term in any known Native dialect.

Perhaps the most fanciful explanation is the claim that California was named after a priest — Padre “Cal y Fornia.” No document has ever surfaced to confirm the existence of this imaginary holy man.

What remains, stripped of conjecture, is this: California entered history through literature, traveled by rumor, and only later settled into geography. Its name was not discovered. It was imagined — and then believed.

Bibliography | Notes

Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España.

Garci Ordóñez de Montalvo. Las Sergas de Esplandián. Seville, 1510.