Origins of the Pico Family

California

Among the young travelers on the second Anza expedition was José María Pico, a boy whose journey alongside his family would ultimately intertwine with California’s history. On this arduous trek, he met his future wife, María Eustaquia Gutiérrez. Eustaquia, just four years old, traveled with her widowed mother, María Feliciana Arballo, and her six-year-old sister, Tomasa. As historian Helen Tyler eloquently noted in 1953, “Fate had ordained that the union of these two pioneers would, in later life, carry the name of Pico onto the pages of every 19th-century history of California.”

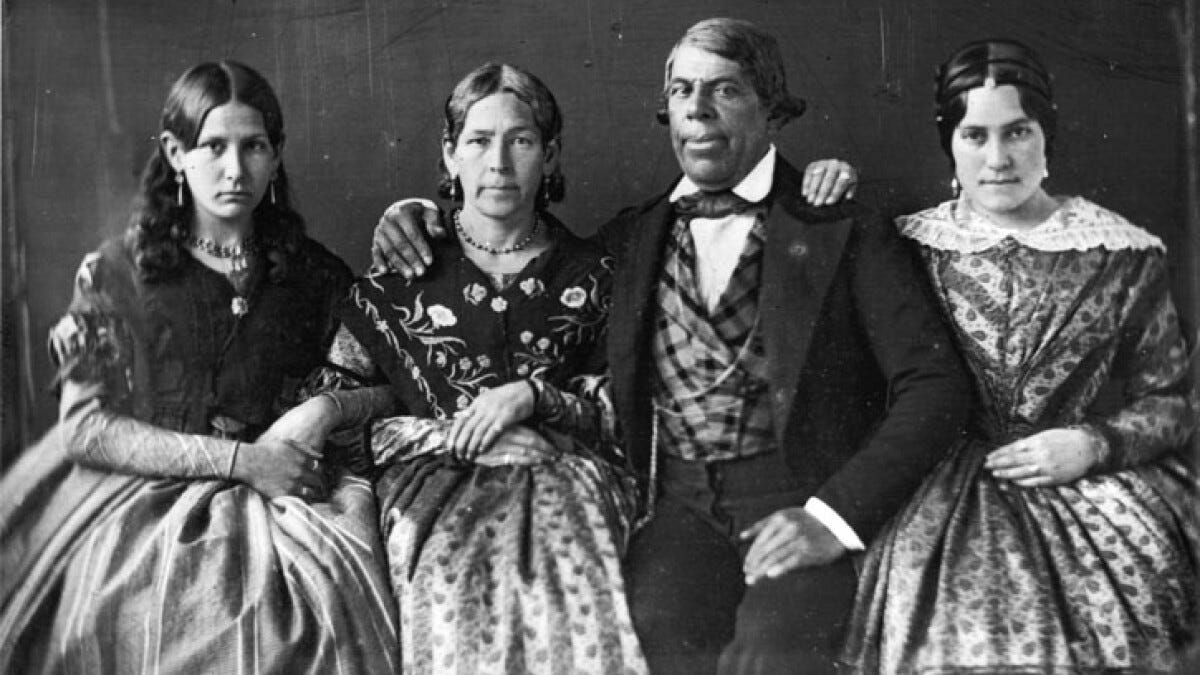

Eustaquia’s future father-in-law, Private Santiago de la Cruz Pico, was another pivotal figure on the expedition. Born in 1733 in Horcasitas, Sonora, Santiago joined the Anza expedition as a soldier recruit, driven to secure new opportunities for his family. By this time, Santiago was married to María Jacinta Bastida and was already the father of seven children, all born in San Javier de Cabazan, Sonora. His participation in Anza’s journey laid the foundation for the Pico family’s rise to prominence, illustrating how those who dared to traverse its rugged frontier planted the seeds of California’s future.

Santiago and his family were classified as gente de razón, a term that distinguished European settlers and their descendants from Indigenous populations within the Spanish colonial framework. This designation, encompassing individuals of mixed ancestry (mestizo) or assimilated Indigenous people, signified alignment with the Spanish language, Catholicism, and societal norms. The term carried significant implications, elevating colonists' social and legal status within the rigid hierarchy of colonial society. It also implied a stark contrast with Indigenous groups, who were often labeled gente sin razón—“people without reason.” The classification of gente de razón shaped the Pico family’s trajectory and underscored the dynamics of colonial identity and power. Santiago’s role in the expedition and his family’s eventual prominence highlights how colonial categories, opportunities, and migrations forged connections that would ripple through California’s history, blending personal ambition with broader societal transformations.

Santiago de la Cruz Pico completed his ten-year military service enlistment by 1786, marking the end of a career that had brought him and his family from Sonora to the Pueblo of Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, which had been founded five years earlier under the direction of Governor Felipe de Neve. As one of the early settlers of the fledgling pueblo, Pico played a role in the community’s development, aligning his family’s future with the opportunities afforded by the expanding frontier of Alta California. After retiring from military service in 1786, Santiago officially moved his family to Los Angeles, where their ambitions as landowners were soon realized. Governor Diego Borica granted Santiago the extensive Rancho San José de Gracia de Simi, a sprawling 92,341-acre tract of land. The grant represented a significant reward for Santiago’s service and loyalty, but came with stipulations. Chief among them was the requirement that Santiago continue to reside in Los Angeles, ensuring his proximity to the region's social and administrative hub.

Though Santiago’s second eldest son, José María Pico, might have been expected to inherit the property, the rancho was formally allocated to three of Santiago’s younger sons—Francisco Javier, Patricio, and José Miguel Pico. At the time, all three were active soldiers in the Santa Barbara company, displaying the enduring military ties of the Pico family and the importance of service to the Spanish Crown in securing land and status. The granting of Rancho San José de Gracia de Simi marked a turning point for the Pico family, or at least for some, solidifying their place among the landed elite of Alta California. It also underscored the complex interplay of military service, land grants, and colonial governance that shaped the region's social fabric. The Picos’ trajectory from soldiers and settlers to prominent landowners encapsulates the opportunities and constraints of life on the Spanish frontier.

In Alta California, land ownership defined social standing and political influence. For José María Pico, however, achieving this cornerstone of success proved elusive. Born in 1765, José María was the founding patriarch of the Pico family of Southern California. At 17, he joined the San Diego Company in 1782, embarking on a military career that would take him to Santa Barbara in 1785 and then to Mission San Gabriel, before returning to San Diego. During his time at Mission San Gabriel, José María became embroiled in a pivotal moment of resistance against Spanish colonial rule. This event would reshape his identity and alter his family’s trajectory.

At the heart of this episode was Nicolás José, a prominent member of the Tongva people, whose ancestral lands encompassed the Los Angeles Basin. A neophyte of Mission San Gabriel, Nicolás José had converted to Catholicism and adopted Spanish customs under the mission system. However, his time at Mission San Gabriel exposed him to the harsh realities of colonial oppression—the suppression of Tongva culture, language, and autonomy. Disillusionment grew into defiance, and by 1785, Nicolás José was orchestrating a coordinated uprising to expel the Spanish colonists.

He allied with Toypurina, a woman revered as a Tongva leader and shaman, to rally local villages into a unified force capable of overwhelming the Spanish presence. Their plan, bold in scope, sought to strike directly at the heart of colonial power by attacking the mission friars. It might have succeeded had it not been for José María Pico. Fluent enough in the Tongva language, José María overheard whispers of the conspiracy and revealed the plan to the Spanish authorities. Soldiers hid in the friars’ quarters, setting a trap that foiled the uprising before it could gain momentum. Nicolás José and his co-conspirators were swiftly apprehended, and the rebellion collapsed.

For José María Pico, this act of loyalty to the Spanish Crown was transformative. In the aftermath of the uprising, he was rewarded for his heroics. The 1785 census reclassified him from mestizo to Español. This status change elevated his social standing and set the stage for his descendants to achieve political and economic prominence in Southern California. This pivotal moment allowed José María to transcend the rigid Sistema de castas, rewriting his identity and securing a legacy that would culminate in the rise of his sons, Pío and Andrés Pico, as major figures in 19th-century California.

For Nicolás José, however, the consequences were dire. Convicted of his role in the rebellion, he was exiled to a distant presidio and sentenced to hard labor. Yet, his defiance symbolized the enduring resistance of the Tongva and other Indigenous peoples against colonial rule. Even in the face of severe punishment and systemic suppression, the uprising underscored a broader truth: Native resistance to Spanish colonization would persist, fueled by the unyielding determination to preserve their way of life. This clash between José María Pico and Nicolás José revealed two diverging paths in Alta California’s colonial history—one of assimilation and social advancement within the colonial system, the other of defiance and enduring resistance against it.

By the time José María Pico returned to San Diego, the little girl he remembered from the Anza expedition, María Eustaquia Gutiérrez, had grown into a captivating beauty. Their childhood bond transformed into a courtship, and José María became her devoted suitor. After the marriage banns were announced on three successive Sundays, the couple wed on May 10, 1789, in the Presidio chapel of San Diego. Remarkably, it was only the second “white” or Español wedding recorded there, a designation that belied their origins—José María as a mestizo and María Eustaquia as a mulata. Their union reflected the fluidity of social identity on the Alta California frontier, where ambition and loyalty to the colonial system could transcend rigid caste boundaries.

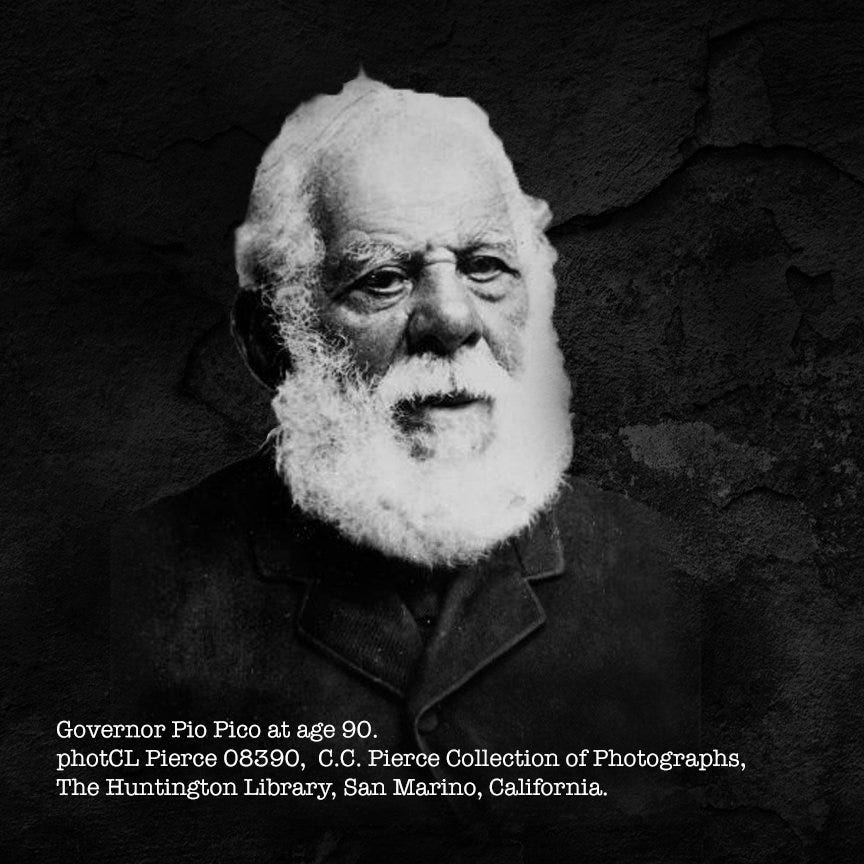

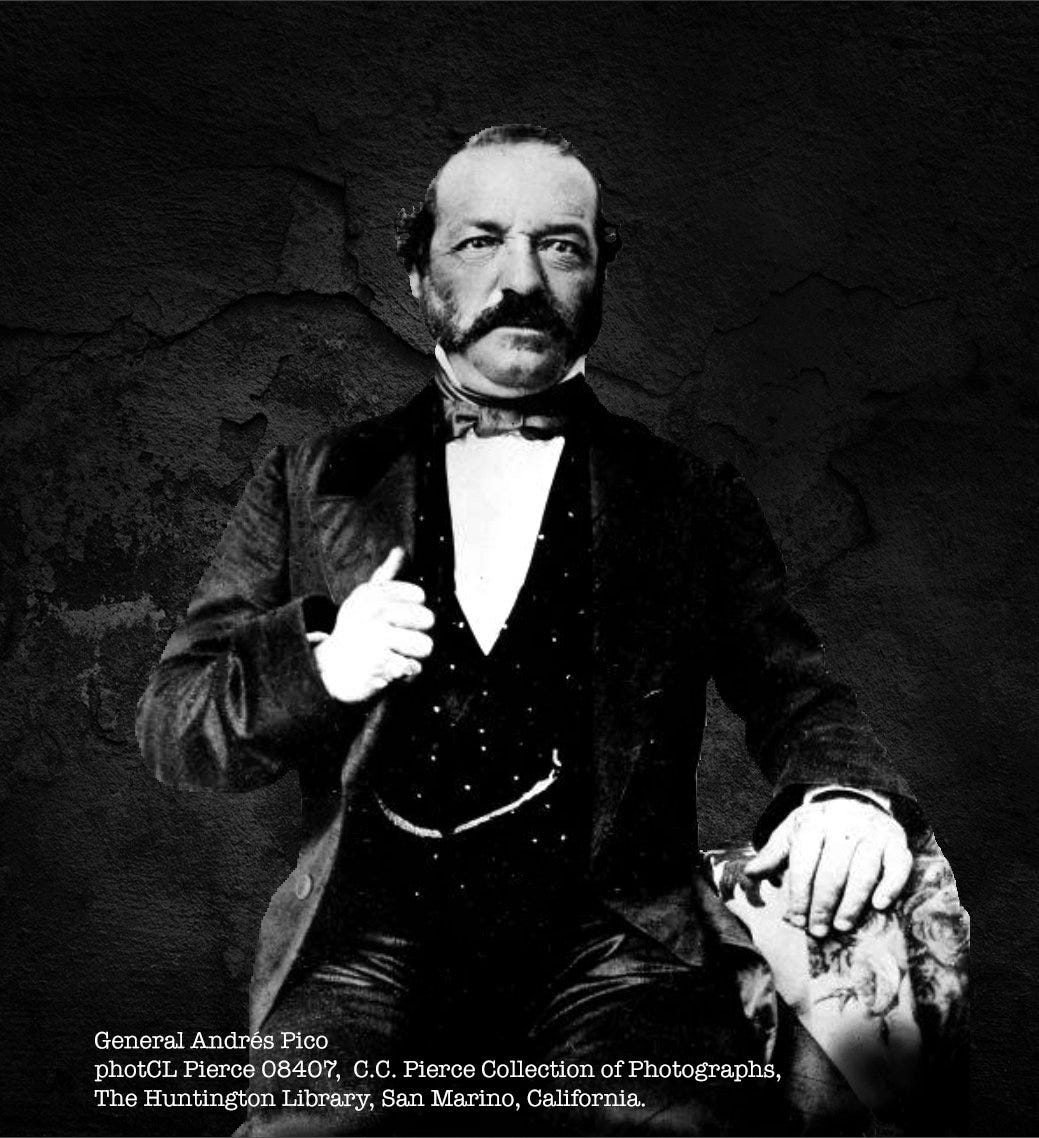

José María rose through the ranks of the Spanish military, achieving the rank of corporal in 1798. That year, he commanded an escort (escolta) for the founding of Mission San Luís Rey in what is now Oceanside, California. By 1800, he was reassigned to Mission San Gabriel as corporal of the guard. It was during his time at San Gabriel that two of his most influential sons were born: Pío de Jesús Pico IV in 1801, who would become Alta California’s final Mexican governor, and Andrés Pico in 1810, a future general and political leader during the American period.

Their births occurred against the backdrop of a world aflame with revolution. By 1811, the insurgency sparked by Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos in New Spain had sent shockwaves across the Spanish Empire, including its farthest reaches in Alta California. This growing unrest seeded distrust among colonial authorities, casting suspicion even on loyal soldiers like José María. That same year, he found himself implicated in a conspiracy to overthrow the San Diego Presidio, accused of aligning with the Mexican cause against the Spanish Crown. The plot was quickly discovered, and José María was arrested—a dramatic turn that placed him on the other side of the rebellion.

The intervention of mission padres proved crucial. They advocated for José María, securing his exoneration and pardon three days later. This leniency was less a reflection of justice and more a strategic attempt to preserve fragile colonial loyalty in Alta California, during a time of escalating unrest. Nevertheless, José María’s arrest became emblematic of the broader revolutionary tremors shaking the empire. His case revealed how the distant echoes of rebellion in Mexico reverberated even in the farthest corners of the Spanish world, where fear and suspicion undermined trust and stability.

Though spared harsh punishment, José María paid a quieter but enduring price for his alleged involvement. Unlike others who faced imprisonment or death—Pío Pico would later recall how artilleryman Ignacio Zúñiga was kept “in chains until independence was achieved” a decade later—José María’s punishment was more insidious. He was never granted land, the ultimate marker of status and success in Alta California. Nor was he afforded early retirement from military service.

José María Pico’s fate as a landless soldier shaped his legacy in subtle but profound ways. His inability to claim the trappings of social prestige—land and autonomy—highlighted the precarious position of those caught in the shifting allegiances of a crumbling empire. Yet, his endurance and resilience would pave the way for his sons to rise as significant figures in 19th-century California, bridging the era of Mexican governance and the arrival of American power. His story is a testament to the complexities of identity, loyalty, and survival on the Alta California frontier during one of the most turbulent periods in its history.

Slow Redemption

By 1815, José María Pico, weary from decades of military service, sought to retire and move his family to San Gabriel while awaiting discharge. But the discharge never came. His request was denied, likely due to lingering distrust from his past involvement in a rebellion and his unique ability to manage Native-Spanish relations. As Alta California simmered amid the turmoil of revolution, a new threat arose in the form of Hippolyte Bouchard—a French-born Argentinian privateer and pirate who, with ambitions of personal gain and destabilizing Spanish rule, targeted the coastline of Alta California.

Having recently met with King Kamehameha I in Hawaii, Bouchard landed in Monterey in 1818 and launched a campaign of terror up and down the coast. In response to this crisis, José María was ordered from San Gabriel to San Diego to organize defenses at the presidio. His leadership shone during this moment of uncertainty. With calm precision, he orchestrated the evacuation of women and children inland to the safety of the Mission of Pala, a mission he carried out with remarkable efficiency. Yet, his preparedness ultimately proved unnecessary. Possibly deterred by organized efforts near Monterey, Bouchard’s men bypassed San Diego and departed Alta California in January 1819.

Though his heroics in defense of the presidio went untested, José María’s readiness reflected his enduring commitment to duty. It was another instance of his steadfast service, but one that could not restore the trajectory of his life. On September 4, 1819, José María passed away at the age of fifty-five, leaving behind no land, no wealth, and little more than hope for the future of his family. His sons would inherit not material prosperity but an unfulfilled legacy and the drive to shape their destinies.

Pío Pico later recalled the stark reality of his father’s death, stating, “Nothing was left us—even an inch of ground.” This truth would become a driving force for Pío and his brother Andrés. The promise of land and the dignity their father had sought became a rallying cry for them. Pío’s political ambitions and Andrés’s readiness for rebellion were fueled by a determination to honor their father’s sacrifices and to ensure their family’s rightful place in Alta California. They refused to relive the frustrations of their father’s life, instead committing themselves to a future without the contingencies that had constrained him.

At the time of his father’s death, Andrés Pico was just eight years old. His mother, María Eustaquia, now widowed and impoverished, faced the daunting task of raising seven children alone. She moved the family from San Gabriel back to San Diego, a place more familiar to her. But when they arrived, they found the presidio in ruins, neglected in the years since her husband’s departure. With no income and little protection, the family struggled to survive.

Eustaquia’s eldest son, Pío, stepped into a leadership role at eighteen. Determined to rebuild their legacy, he started a small store selling groceries, liquor, furniture, and clothing. It was a modest beginning but marked the start of the Pico family’s ascent from poverty to prominence. Through Pío’s political savvy and Andrés’s eventual military and diplomatic success, the Pico family would fulfill the promise of Alta California—a legacy forged from the lessons and trials of their father’s life.

José María Pico’s story reflects the layered complexities of Alta California during a time of global revolution and change. His life revealed how local power could be wielded effectively even under colonial constraints. Still, it also underscored the harsh realities of a system that often left even its most loyal servants unrewarded. His sons would learn from his triumphs and his frustrations, taking bold steps to ensure their family’s future and, in doing so, shaping the history of Alta California during its transformative years.

Pío Pico’s entrepreneurial spirit emerged early, as he took on the role of breadwinner for his family, making regular trips between Los Angeles and Baja California to barter goods and livestock. His ambition set the tone for the Pico household, but it was not unique among Eustaquia’s children. Eustaquia instilled a deep sense of industriousness and resilience in her family. She and her sister, Tomasa, taught the younger girls the art of needlework, enabling them to contribute financially to the family’s future. Together, the family saved toward their dream of independence and a home.

That dream became a reality in 1824 when Pío and Andrés Pico constructed what was celebrated as the finest adobe on San Diego’s Presidio Hill. Built with their own hands, the house was a testament to their ambition and skill. It featured “two large front living rooms, three additional rooms at the front, and a backyard with a kitchen, two rooms with southern-facing doors, and a bathroom.” The adobe’s impressively thick walls and meticulous craftsmanship reflected exceptional care and attention to detail. Described as “more beautiful than any adobe in paradise itself,” the home symbolized a major milestone for the Pico family, signaling their arrival as a socially and politically prominent force in San Diego and Los Angeles during the 1820s.

The family’s rise coincided with seismic shifts in Alta California’s political landscape. In 1822, news of Mexico’s victory in its war for independence reached the region, bringing both optimism and uncertainty. The old Spanish alliances were gone, replaced by the fledgling structures of the Mexican Republic. For emerging families like the Picos, the early years of Mexican rule offered an opportunity to gain recognition and assume leadership in the rapidly changing society of Los Angeles.

The transition to Mexican governance economically proved advantageous for the industrious Pico brothers. The lifting of trade restrictions under Mexico opened Alta California to the broader Pacific economy, creating a boom in commerce that extended beyond local markets. The hide and tallow trade, in particular, became a cornerstone of the region’s prosperity, attracting international traders to Alta California’s shores. With its vast plains stretching from the San Fernando Valley to the Los Angeles Basin, Los Angeles became a cattle ranching hub. The port of San Pedro facilitated the export of hides and tallow, turning cattle into economic powerhouses. For the Picos, this thriving industry presented endless opportunities to build wealth and influence. By the 1820s, their economic ventures, combined with their social and political ascendance, positioned them as key figures in the evolving landscape of Alta California—poised to shape its future in the Mexican era.

Politically, in the early part of the 1820s, under the new Mexican Republic, local representatives were so often overruled by commanders that officials of the republic changed how things were to be done at the regional level. In 1822, an opportunity that allowed the power to rest in the hands of the people was instituted, where the property owners of Los Angeles could now elect an ayuntamiento, a civilian town council, to handle affairs. Even so, there were those like the Presidio of Santa Barbara military commander, Lieutenant José de la Guerra y Noriega, who did their best to stop such changes by ignoring directives and appointing a comisionado (or a commissioner) as had been tradition under the authority of officials in New Spain.

By 1825, the people had enough of de la Guerra, leading to protests against the governor. The people demanded “that their civilian authority be respected” and opposed “the ongoing appointment of a comisionadodespite the theoretical abolition of the post.” The feelings of rebellion were finally externalized by Pío Pico when in 1827. In the unfolding dramas of Mexican California in the early nineteenth century, it was not always a grand military campaign or a formal decree that stirred the first sparks of independence in a young heart. Sometimes, an offhand remark—cutting, irreverent, and aimed at the heart of authority—could ignite a moment of self-realization.

In recalling this episode in his later years in an oral interview on October 24, 1877, conducted by Thomas Savage and later published in Don Pio Pico’s Historical Narrative, one can almost see the subtle but decisive shift occurring within the young Pío Pico, long before his name would be fixed in California’s annals as a prominent landowner and political figure. It was a shift from dutiful obedience to a more complex understanding of freedom, citizenship, and the fragile dignity of the individual.

At the time, Pico served as scribe to Captain Don Pablo de la Portilla, an officer tasked with extracting a sworn declaration from a certain Señor Bringas, a merchant accused of being part of a scandal involving misappropriated public funds in Los Angeles. The merchandise in question, it was said, belonged to a high-ranking sub-commissioner, a man who allegedly diverted government funds intended for the troops in California. Such inquiries were not uncommon in this transitional period; the distant central authority in Mexico City struggled to maintain order in a province that often seemed more autonomous than not. Military men were dispatched to keep the peace, hold men to account, and preserve the hierarchy upon which the state’s legitimacy rested. Their uniforms and commissions demanded respect—at least, that was the prevailing logic.

Yet when Captain Portilla and Pico met the merchant Bringas at an ad hoc office arranged in the home of Don Antonio Rocha, the air changed. Bringas’s refusal to yield and even to recognize the captain as anything more than “the sole of his shoe” must have rattled something deep within Pico’s mind. Until that moment, the entire structure of authority had seemed natural, inviolate. Armies and their captains stood for order. To treat a uniformed officer with such dismissiveness was akin to heresy. Yet Bringas insisted that the true power resided not in the men who wore swords and insignia but in the civilian body, the paisanos—the citizenry. The people were sacred, he said, and the army merely served them. In those stark words, the roles and claims of power spun on their axis. Suddenly, the nation was not defined by those who wielded arms but by those who tilled fields, traded goods, and raised families—the common folk, like the Pico family, who had settled two generations prior. That revelation hung in the room, pressing upon Pico’s young soul as a new truth.

Pico was determined to test this new intellectual currency when he carried a message to the commandant in San Diego. Family needs had drawn him back home to San Diego, and San Diego Captain José María Estudillo called for Pico to return to Los Angeles now felt like an infringement. He noted his interaction with Captain Estudillo,

“My mother and my family were all in need of my services in San Diego and made it plain to me that for this reason, they were opposed to my return to Los Angeles. I wanted to please my mother and at the same time show my sense of independence. I now considered myself a ‘sacred vessel’ — words which sounded very good to my ears. I presented myself to Estudillo.”

To Pico, if the people were indeed the nation’s core, what gave a military man the right to order him around, to claim precedence over his duty to his mother and kin? Pico refused to comply. The result was swift and humiliating: an order, an arrest, a night in jail. Pico continued in his recollection,

“He had the official letter ready in his hand and he asked me if I was prepared to depart as he handed me the letter. I told him that I was not able to return to Los Angeles as I was needed at home. Then Señor Estudillo issued orders to the sergeant that I should be taken to the jail. They imprisoned me in a cell with other prisoners though I had the luck not to be placed in irons. I was there all that day and that night and the next morning Estudillo ordered my release, and that I should be taken to the commandant’s office.”

If before Pico had watched Bringas’ defiance with a mixture of shock and curiosity, now he experienced firsthand what it meant to challenge military authority. Yet, his confinement only confirmed the transformative idea that had begun to take root. The following day, Commandant Estudillo released Pico and offered a half-hearted apology, characterizing the incarceration as a moment of heated emotion. He bade Pico return to his family duties. Pico recalled,

“I went there and he asked me to excuse the manner in which I had been treated — that it had been a hot-headed action and that I should go and look after my mother. I retired to my home and stayed at my mother's side, but always it appeared to me, deep in my soul, that the citizens were the nation and that no military was superior to us.”

It was too late to restore the old worldview. Pico emerged into the sun of San Diego, a changed man. He would carry with him now the imprint of Bringas’s words: that the legitimacy of government, and by extension, the army, sprang from the civilian mass. Once so fixed and venerable, things no longer seemed ordained from above. Instead, it appeared contingent, dependent on the consent and will of the governed.

This was no dramatic revolt; Pico did not run off to stage an insurrection. But in small, incremental ways, with the help of the equally frustrated Captain Estudillo—first as a private realization, then as a settled conviction, and eventually as a principle guiding his public life—he embraced the notion of liberty as located in ordinary people. What Bringas had introduced and Estudillo enforced into Pico’s mind would linger and mature. And in that subtle shift, in the small crucible of a dusty Californian outpost, we see one man’s early reckoning with the meaning of citizenship and authority. In the quiet spaces of the historical record, beyond the grand speeches and sweeping mandates, it is often such moments—fleeting and personal—that sow the seeds of a more democratic understanding of nationhood and freedom.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bolton, Herbert Eugene. Anza’s California Expeditions. Vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1930.

Chapman, Charles E. A History of California: The Spanish Period. New York: Macmillan, 1921.

Cherny, Robert W., Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo, and Richard Griswold del Castillo. Competing Visions: A History of California. 2nd ed. Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2014.

Deverell, William, and Greg Hise, eds. A Companion to Los Angeles. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Hackel, Steven W. Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Heizer, Robert F., ed. The Missions of California: A Legacy of Genocide. Menlo Park: Ballena Press, 1977.

Los Angeles Ayuntamiento. Letter to Lieutenant José de la Guerra y Noriega, March 26, 1825. Los Angeles City Archives, vol. 2, 1821–1835.

Pico, Pío. Don Pío Pico’s Historical Narrative. Translated by Arthur Botello, edited with an introduction by Martin Cole and Henry Welcome. Arthur H. Clark Company, 1973.

Rawls, James J., and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012.

Salomon, Carlos Manuel. Pío Pico: The Last Governor of Mexican California. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Tyler, Helen. “The Family of Pico.” The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly 35, no. 3 (1953): 221–238.