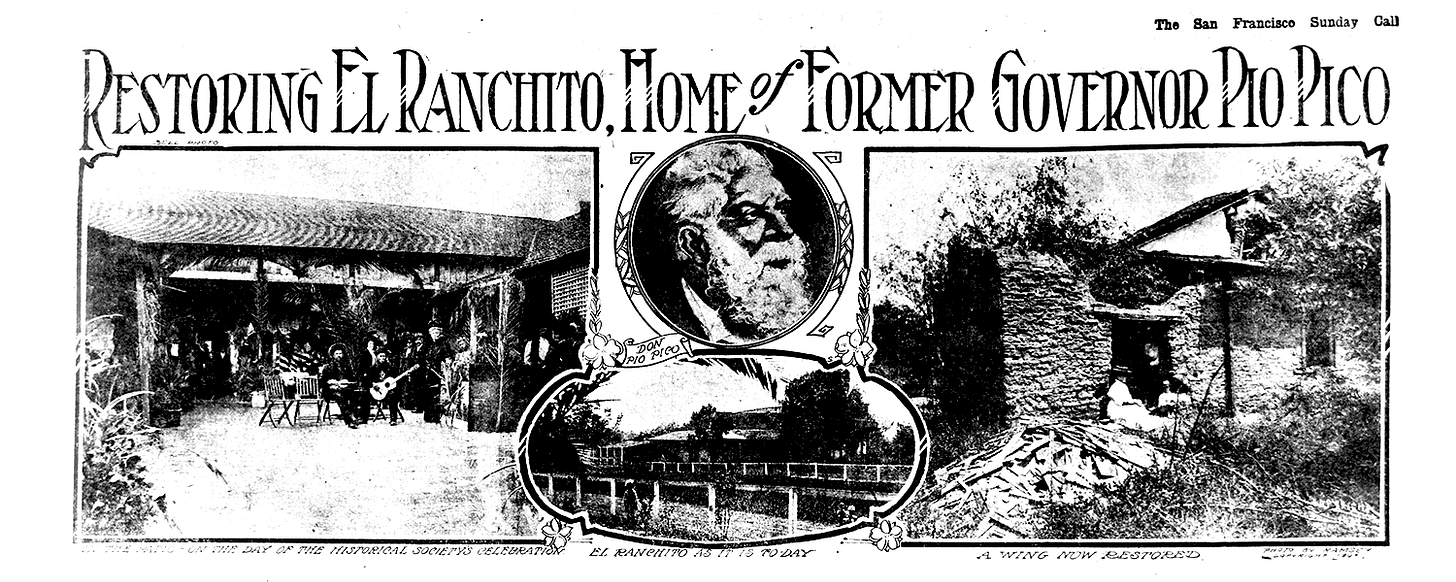

Restoring El Ranchito, Home of Former Governor Pío Pico

California

By Alfred Dezendorf

Hard by the little city of Whittier, in Southern California, there stands the old home of Don Pío Pico, California’s last governor under Mexican rule. The weather-beaten facade of this old adobe, which in its palmy days was known as the largest residence in the state, looks into the waters of Mission Creek, a little stream that hurries across the ancient highway, El Camino Real, scarcely a hundred feet away. The oldest part of this mansion of the pastoral days, remarkable as the first two-story adobe residence erected in California, was built in 1826. The property became Don Pío’s in 1832, and although it was said of him that his lands were so vast that he could travel the length of the state and stop each night at his own hacienda, El Ranchito, as he fondly named this home, remained his favorite throughout his later years, despite being the smallest of his vast holdings.

It was not far from this rancho, at the San Gabriel Mission, that Don Pío was born in 1801, of French and Mexican parentage. Both he and his brother, Don Andrés Pico, were representative figures of the Californio era—hospitable, generous to a fault, and lovers of horse racing and the gaming table. They lived like princes on their vast estates in Santa Barbara, San Diego, and Los Angeles counties. During his political career, Don Pío amassed considerable land, sometimes by fair means, sometimes otherwise, and often gifted large tracts to his friends, many of whom later found themselves embroiled in litigation over ownership.

A Governor’s Rise and Fall

Don Pío Pico first became governor of Alta California under Mexican rule in 1832, taking the oath at the old Mission Church on the Los Angeles Plaza, administered by General Vallejo. That same year, he acquired El Ranchito. The house, with its long, deep-windowed rooms surrounding a central patio, was once resplendent with life. By 1870, the estate had 33 rooms, and the patio was shaded by a giant black fig tree, its red-brick courtyard filled with rare flowering plants. A deep well, an old mill, and a great Dutch oven—all essential parts of a grand casa in those days—stood nearby.

In 1834, Don Pío married Doña Maria Ignacio Alvarado at the Carrillo house in Los Angeles, in a wedding feast that lasted eight days, attended by the Californio aristocracy from San Diego to Monterey. The couple had no children, and Doña Maria died years before Don Pío.

Pico’s first term as governor ended in 1833, but he returned to power in 1845, following the bloodless conflict at Cahuenga Pass, which ousted Governor Micheltorena. His authority was recognized until the American occupation in 1846. When Commodore Stockton entered Los Angeles, Don Pío and General José Castro fled to Sonora, evading American forces.

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), Pico returned, residing at his brother’s estate in San Fernando. In the 1850s and ’60s, he spent most of his time at Santa Margarita Rancho, though El Ranchito remained in his possession.

The Loss of an Empire

Gertrude Atherton, in her book The Splendid Idle Forties, described Pico as "hung with chains and ropes of gold and jewels". Though not a handsome man, his extravagant appearance was legendary. He rode through the countryside on a blooded steed, his saddle and bridle jingling with silver decorations. His pockets were filled with $50 gold pieces, which he spent lavishly.

Whether at cockfights or horse races near San Gabriel Mission, Don Pío was always at the center of the action, bringing his fastest horses from Santa Margarita. He and his brother were famous for graceful dancing at fandangos, where the sounds of guitars and the rushing waters of the creek mingled beneath the moonlight.

However, such extravagant living could not last forever. Pico, like many Californio landowners, lost his vast estates—which today would be worth $50 million—to American land speculators and legal manipulations. In the 1880s, Pico signed a blanket mortgage for $95,000 to three American lenders, unknowingly deeding away El Ranchito due to his poor English skills. A court ruling stripped him of his beloved hacienda, and his wealth vanished. By the time of his death at age 93 in 1894, Pico lived in a small house in Los Angeles, the gift of an American friend.

Saving a Californio Landmark

Meanwhile, El Ranchito, once a grand estate, fell into ruin. By the early 20th century, the chapel had been demolished, its bricks used to repair the road. The house itself was slated for destruction, until Mrs. H.W.R. Strong and other women in Whittier took action.

They enlisted the support of Charles Lummis and the Landmarks Club, forming the Pío Pico Historical Society in 1907. Their goal was to acquire, restore, and preserve El Ranchito. In 1909, they secured a 50-year lease from the City of Whittier, which had purchased the estate as a water-bearing property.

Though hindered by limited funds, the society spent $1,000 on initial restorations. They braced the walls and roof, restored the patio, and added 200 feet of cement foundation. However, much remained to be done—windows, doors, new flooring, roof repairs, plastering, and landscaping.

A Triumph of Preservation

On March 19, 1909, El Ranchito held its first major gathering in 40 years. The Pío Pico Historical Society celebrated their progress with a traditional Spanish barbecue. Over 1,000 guests attended, enjoying an ox cooked a la Mexicana by famed chef Joe Romero. The crowd consumed 550 pounds of beef, 50 gallons of Spanish beans, and five gallons of chile rojo sauce. 400 quarts of coffee washed down enchiladas and tamales, as a Spanish orchestra played under the old ash tree that Don Pío himself had planted.

Speakers reminisced about Pico’s generosity, his deep love for Spain, and his eventual loyalty to the United States.

The Pío Pico Historical Society continued its work, planning to transform the drawing room into a museum filled with Pico family heirlooms, including the safe that once held California’s state papers. Memberships were offered for $25, with funds directed toward preserving one of California’s most significant landmarks.

Today, El Ranchito stands as a symbol of California’s Mexican past, a testament to the resilience of history—thanks to a dedicated group of Whittier women, who saw the importance of honoring the last Mexican governor’s legacy.

🦶🎵: Alfred Dezendorf, "Restoring El Ranchito, Home of Former Governor Pío Pico," The San Francisco Call (08 Aug. 1909): p. 4.